Trees – Guardians of the Earth

By Bill Mollison

What I hope to show is the immense value of trees to the biosphere. We must deplore the rapacity of those who, for an ephemeral profit in dollars, would cut trees for newsprint, packaging and other temporary uses. When we cut forests, we must pay for the end cost in drought, water loss, nutrient loss and salted soils. Such costs are not charged by uncaring or corrupted governments and deforestation has therefore impoverished whole nations.

The process continues with acid rain as a more modern problem, charged against the cost of electricity or motor vehicles, with the inevitable account building up so that no nation can pay, in the end, for rehabilitation. The capitalist, communist and developing worlds will all be equally brought down by forest loss.

Those barren political or religious ideologies which fail to care for forests carry their own destruction as lethal seeds within their fabric.

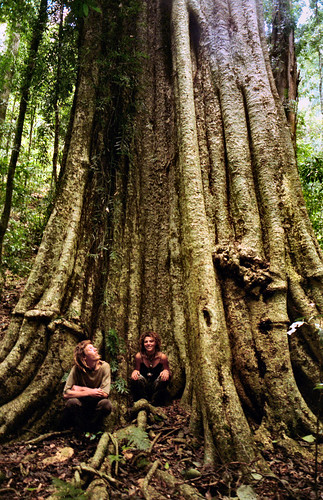

We should not be deceived by the propaganda that promises for every tree cut down, a tree planted. The exchange of a fifty gram seedling for a forest giant of fifty to twelve hundred tonnes is like the offer of a mouse for an elephant. A young forest or tree doesn’t behave like the same entity in age; it may be more or less frost hardy, wind fast, salt tolerant, drought resistant or shade tolerant at different ages and seasons.

I can never see the forest as an assemblage of plant and animal species, but rather as a single body with differing cells, organs and functions. A forest is not just a number of trees. A forest and its animals is a complex and interdependent organism.

At the crown of the forest and within its canopy, the cast energies of sunlight, wind and precipitation are being modified for life and growth. Trees not only build but conserve the soils, shielding them from the impact of raindrops and the wind and sun.

At the crown, forceful raindrops are broken up and scattered, often to mist, or coalesced into small bark-issued streams and so descend to earth robbed of the kinetic energy that destroys the soil mantle outside forests. Further impedance takes place on the forest’s floor, where roots, litter, logs and leaves redirect, slow down and pool the water.

Like all living things, a tree has shed its weight many times over to earth and air, and has built much of the soil it stands in. Not only the crown, but also the roots die and shed their wastes to earth. The living tree stands in a zone of decomposition, much of it transferred, reborn, transported, or reincarnated into grasses, bacteria, fungus, insect life, birds and mammals.

The root fungi intercedes with water, soil and atmosphere to manufacture cell nutrients for the tree, while myriad insects carry out summer pruning, decompose the surplus leaves and activate essential soil bacteria for the tree to use for nutrient flow. The rain of insect faeces may be crucial to forest and prairie health. It is a clever person indeed who can separate the total body of the tree into mineral, plant, animal detritus and life. This separation is for simple minds as its total entity, like ours, reaches out into all things.

How a Tree Interacts With Rain

When rain falls on a forest, a complex process begins. First the tree canopy shelters and nullifies the impact of raindrops, reducing the rain to a thin mist below the canopy even in torrential showers.

When rain falls on a forest, a complex process begins. First the tree canopy shelters and nullifies the impact of raindrops, reducing the rain to a thin mist below the canopy even in torrential showers.However, if more rain falls, water commences to drift as mists or droplets to earth. This water is called ‘throughfall’.

As an average figure, the throughfall is 85% of rain in humid climates. At this point, throughfall contains many plant cells and nutrients and is a much richer brew than rainfall. Dissolved salts, organic content, dust and plant exudates are included in the throughfall.

The random fall of rain is converted into well-directed flow patterns that serve the needs of growth in the forest. In the stem bases of palms, plantains and many epiphytes or the flanged roots of figs, water is held as aerial ponds, often rich in algae and mosquitoes. Stem mosses and epiphytes absorb many times their bulk of water, and the tree itself directs water via in-sloping branches and fissured bark to its tap roots, with spiders catching their share on webs and fungi soaking up what they need. Some trees trail weeping branches to direct throughfall to their fibrous peripheral roots.

With the aerial reservoirs filled, the throughfall now enters the humus layer of the forest, which can itself (like a great blotter) absorb one centimeter of rain for every centimeter of depth. In undisturbed rainforest, deep mosses may carpet the forest floor. For 40-60 centimetres in depth, the throughfall is absorbed by the decomposers and living systems of the humus layer. Again, the composition of the water changes, picking up humic exudates, and water from the deep forests and bogs may take on a clear golden colour, rather like tea.

Below the humus lie the tree roots, each enclosed in fungal hyphae and gels secreted by bacterial colonies. Thirty to forty percent of the tree itself lies in the soil; most of this extends over many acres, with thousands of kilometres of root hairs lying mat-like in the upper sixty centimetres of soil (only 10% to 12% of the root mass lies below this depth but the remaining roots penetrate as much as forty metres into the rocks below). The root mat actively absorbs the solution that water has become, transporting it up the tree again to transpire to air.

If we imagine the visible (above-ground) forest as water (and all but five to ten percent of this mass is water), and then imagine the water contained in soil humus and root material, the forests represent great lakes of actively managed and actively recycled water.

Thus the soil becomes an impediment to water movement and the free (interstitial) water can take as long as one to forty years to percolate through to streams. It almost seems as if the purpose of the forests is to give the soil time and the means to hold fresh water on land.

On bare soils and thinly spaced or cultivated crops, the impact of droplets carries away soil and many rains typically remove thirty tons per acre, or up to five hundred tons in extreme downpours. When we bare the soil we lose the earth.

Wind Effects

Vogel (1981) notes that as wind speed increases, the tree’s leaves and branches deform so that the tree steadily reduces its exposed leaf area. Vogel notes that very heavy and rigid trees spread wide root mats, and may rely totally on their weight, withstanding considerable wind force with no more attachment than that necessary to prevent slide, while other trees insert gnarled roots deep in rock crevices and are literally anchored into the ground.

The forest bends and sways, each species with its own amplitude.

Apart from the moisture, the wind may carry heavy loads of ice, dust or sand. Stand trees (palms, pines and casuarinas) have tough stems or thick bark to withstand wind particle blast. Even tussock grasses slow the wind and cause dust loads to settle out. In the edges of forests and behind beaches, tree lines may accumulate a mound of driven particles just within their canopy. The forest removes very fine dusts and industrial aerosols from the airstream within a few hundred metres.

Forests provide a nutrient net of material blown by wind, or gathered by birds that forage within its edges. Migrating salmon in rivers die in the headwaters after spawning and thousands of tonnes of fish remains are deposited by birds and other predators in the forests surrounding these rivers. In addition to these nutrient sources, trees actively mine the base rock and soil for minerals.

Trees and Precipitation

Trees have helped to create both our soils and our atmosphere. The first by mechanical (root pressure) and chemical (humic acid) breakdown of rock, adding life processes as humus and myriad decomposers.

Trees have helped to create both our soils and our atmosphere. The first by mechanical (root pressure) and chemical (humic acid) breakdown of rock, adding life processes as humus and myriad decomposers.The second by gaseous exchange, establishing and maintaining an oxygenated atmosphere and an active water vapour cycle essential to life.

The composition of the atmosphere is the result of reactive processes, and forests may be doing about eighty percent of the work, with the rest due mainly to oceanic or aquatic exchange. Many cities, and most deforested areas such as Greece, no longer produce the oxygen they use.

The basic effects of trees on water vapour and windstreams are; * Compression of streamlines, and induced turbulence in airflows. * Condensation phenomena, especially at night.

Moisture will not condense unless it finds a surface to condense on. Leaves provide this surface, as well as contact cooling. Leaf surfaces are likely to be cooler than other objects at evening due to the evaporation from leaf stomata by day. As air is also rising over trees, some vertical lift cooling occurs, the two combining to condense moisture on the forest.

A single tree such as a giant Til (Ootea foetens) may present forty acres of laminate leaf surface to the sea air, and there can be forty or so such trees per surface acre; trees enormously magnify the available condensation surface.

Who has not stood under a great tree which rains softly and continuously at night on a clear and cloudless evening? Some gardens, created in these conditions, quietly catch their own water while neighbours suffer drought.

The effects of condensation by trees can be quickly destroyed. Felling of the forests causes rivers to dry out and drought to grip the land. All this can occur within the lifetime of a person.

Windstreams flow across a forest. The streamlines are partially deflected over the forest (almost sixty percent of the air) and partly absorbed into the trees (about forty percent of the air). Within a thousand metres the air entering the forest, with its tonnages of water and dust, is brought to a standstill. The forest has swallowed these great energies, and the result is an almost imperceptible warming of the air within the forest, a general increased humidity in the trees (averaging 15% to 18% higher than the ambient air) and air in which no dust is detectable.

Under the forest canopy, negative ions produced by the life processes cause dust particles (++) to clump and adhere to each other and a fallout of dispersed dust results.

If… hot air enters the forest, it is shaded, cooled, de-humidified and slowly released via the crowns of the trees. We may see this warm humid air as misty spirals ascending from the forest. The trees modify extremes of heat and humidity to a life-enhancing and tolerable level.

The winds deflected over the forest cause compression in the streamlining of the wind, an effect extending to twenty times the tree height, so that a twelve metre (forty foot) high line of trees compresses the air to 240 metres (eight hundred feet) above, creating more water vapour per unit volume and cooling the ascending air stream. Both conditions are conducive to rain.

These saturated airstreams condense in trees to create a copious soft condensation which, in such conditions, may far exceed the precipitation caused by rainfall. Condensation drip can be as high as 80%-85% of total precipitation on the upland slopes of islands or seacoasts, and eventually produces the dense rainforests of Tasmania, Chile, Hawaii, Washington-Oregon and Scandinavia. It produced the redwood forests of California and the giant laurel forests of the pre-conquest Canary Islands (now an arid area due to almost complete deforestation by the Spanish).

Re-Humidifying Airstreams

Forests are cloud makers both from water evaporated from the leaves by day and water transpired as part of life processes. A large evergreen tree such as Eucalyptus globulus [Blue Gum] may pump out eight hundred to a thousand gallons of water and returned to the air to become clouds.

A forest can return (unlike the sea) 75% of its water to air, in large enough amounts to form new rain clouds (Bayard Webster, Forests Role in Weather; documented in Amazon, New York Times section 5-7-83). Forested areas return ten times as much moisture as bare ground, and twice as much as grasslands.

This is a crucial finding that adds even more data to the relationship between desertification and deforestation.

Of the 75% of water returned by trees to air, 25% is evaporated from leaf surfaces and 50% transpired. The remaining 25% of rainfall infiltrates the soil and eventually reaches the streams, or evaporates to air. Over the forests, twice as much rain falls than is available from the incoming air, so that the forest is continually recycling water to air and rain, producing fifty percent of its own rain (Webster, Ibid). These findings forever put an end to the fallacy that trees and weather are unrelated [More recent research shows the pivotal role of old growth trees in uplifting deeply stored deuterium-rich heavy water and concentrating it in the atmosphere, causing precipitation – Ed].

Design strategies are obvious and urgent – save all forest that remains and plant trees for increased condensation on the hills that face the sea.

All these factors are clear enough for any person to understand. To doubt the connexion between forests and the water cycle is to doubt that milk flows from the breast of the mother, which is the analogy given to water by tribal peoples. Trees were the hair of the earth which caught the mists and made the rivers flow. Such metaphors are clear allegorical guides to sensible conduct, and caused the Hawaiians (who had themselves brought about earlier environmental catastrophes) to Tabu forest cutting or even make tracks on high slopes, and to place mountain trees in a sacred or protected category.

In summary, we do not need to accept rainfall as having everything to do with total local precipitation, especially if we live within thirty to one hundred miles of coasts (as much of the world does), and we do not need to accept that total precipitation cannot be changed. Let’s be clear about how trees affect total precipitation. The case taken is where winds blow inland from an ocean or large lake:

1) The water in the air is evaporated from the surface of the sea or lake. It contains a few salt particles but is clean. A small proportion may fall as rain (15%-20%), but most of this water is condensed out of clear night air of fogs by the cool surfaces of leaves (80%-85%). Of this condensate, 15% evaporates by day and 50% is transpired. The rest enters the groundwater. Thus, trees are responsible for more water in streams than the rainfall alone provides. 2) Of the rain that falls, 25% is re-evaporated from crown leaves and 50% is transpired. This moisture is added to clouds, which are now at least 50% tree water. These clouds travel on inland to rain again. Trees may double or multiply rainfall itself by this process, which can be repeated many times over extensive forested plains or foothills.

If we can only understand what a tree does for us, how beneficial it is to life on Earth, we will (as many tribes have done) revere all trees as sisters and brothers.

I hope to show that the little we do know has this ultimate meaning; without trees, we cannot inhabit the Earth. Without trees we rapidly create deserts and drought, and the evidence for this is before our eyes. Without trees, the atmosphere will alter its composition, and life support systems will fail.

- Bill Mollison, the progenitor of Permaculture, wrote this as an early version of a section of his landmark book Permaculture – A Designer’s Manual – a completely indispensable work for anyone living WITH planet Earth, in any climat or situation. A longer version of this article was first printed in Nimbin News, July 1988 and excerpted in NEXUS New Times Magazine, Vol 1, No 6

images by R. Ayana - https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4017/5157362967_e96179c740_b.jpg

https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4097/4736324766_ce893d53f5_b.jpg

https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4123/4736326732_8d09f25f2a_b.jpg

https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4097/4736324766_ce893d53f5_b.jpg

https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4123/4736326732_8d09f25f2a_b.jpg

Hope you like this

not for profit site -

It takes hours of work every day by

a genuinely incapacitated invalid to maintain, write, edit, research,

illustrate and publish this website from a tiny cabin in a remote forest

Like what we do? Please give anything

you can -

Contribute any amount and receive at

least one New Illuminati eBook!

(You can use a card

securely if you don’t use Paypal)

Please click below -

Spare Bitcoin

change?

For further enlightening

information enter a word or phrase into the random synchronistic search box @

the top left of http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

And see

New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

New Illuminati on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/the.new.illuminati

New Illuminati Youtube Channel - http://www.youtube.com/user/newilluminati

New Illuminati on Google+ @ https://plus.google.com/115562482213600937809/posts

New Illuminati on Twitter @ www.twitter.com/new_illuminati

New Illuminations –Art(icles) by

R. Ayana @ http://newilluminations.blogspot.com

The Her(m)etic Hermit - http://hermetic.blog.com

DISGRUNTLED SITE ADMINS PLEASE NOTE –

We provide a live link to your original material on your site (and

links via social networking services) - which raises your ranking on search

engines and helps spread your info further!

This site is published under Creative Commons (Attribution) CopyRIGHT

(unless an individual article or other item is declared otherwise by the copyright

holder). Reproduction for non-profit use is permitted

& encouraged - if you give attribution to the work & author and include

all links in the original (along with this or a similar notice).

Feel free to make non-commercial hard (printed) or software copies or

mirror sites - you never know how long something will stay glued to the web –

but remember attribution!

If you like what you see, please send a donation (no amount is too

small or too large) or leave a comment – and thanks for reading this far…

Live long and prosper! Together we can create the best of all possible

worlds…

From the New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com