The Potential of Local Currency

By Susan Meeker-Lowry

People have always traded and bartered with each other. As economies became more complex, money was created as a more convenient means of exchange. In those early days, money was generally a commodity -- something valued by the people who agreed to use it. Iron nails were used as money in Scotland, dried cod in Newfoundland, sugar in some West Indies Islands, salt in ancient Rome, wampum by Native Americans, corn in Massachusetts in the 1600s. Sometimes money was backed by a commodity: the first Latin coins were stamped with the image of a cow and could be redeemed for cattle.

Paper money was created in the 1700s. It was basically an IOU backed by gold and silver but these standards were abandoned (first in 1933 by President Roosevelt for U.S. citizens, then in 1971 by President Nixon for everyone else), so today our money is backed by nothing but promises (and debt). Thomas Greco, Jr., a community economist and author of New Money for Healthy Communities states that, "The proper kind of money used in the right circumstances is a liberating tool that can allow the fuller expression of human creativity. Money has not lived up to its potential as a liberator because it has been perverted by the monopolization of its creation and by politically manipulating its distribution -- which makes it available to the favored few and scarce for everyone else."

Greco outlines three basic ways in which conventional money malfunctions: there is never enough of it, it is misallocated at its source so that it goes to those who already have lots of it, and it systematically pumps wealth from the poor to the rich. The symptoms of a "polluted" money supply are too familiar: inflation, unemployment, bankrupticies, foreclosures, increasing indebtedness, homelessness, and a widening gap between the rich and the poor. In the U.S. the wealthiest 1 percent of households owns nearly 40 percent of the nation’s wealth; and the top 20 percent (households worth $180,000 or more) have more than 80 percent of the country’s wealth. Edward N. Wolff, an economics professor at New York University says, "We are the most unequal industrialized country in terms of income and wealth, and we’re growing more unequal faster than the other industrialized countries."

Greco outlines three basic ways in which conventional money malfunctions: there is never enough of it, it is misallocated at its source so that it goes to those who already have lots of it, and it systematically pumps wealth from the poor to the rich. The symptoms of a "polluted" money supply are too familiar: inflation, unemployment, bankrupticies, foreclosures, increasing indebtedness, homelessness, and a widening gap between the rich and the poor. In the U.S. the wealthiest 1 percent of households owns nearly 40 percent of the nation’s wealth; and the top 20 percent (households worth $180,000 or more) have more than 80 percent of the country’s wealth. Edward N. Wolff, an economics professor at New York University says, "We are the most unequal industrialized country in terms of income and wealth, and we’re growing more unequal faster than the other industrialized countries."In many communities around the country people are taking control by creating their own currency. This is completely legal and, as organizers are finding, often very empowering. The move toward local currency is not only motivated by the desire to bridge the gap between what we earn and what we need to survive financially (although this plays a role, of course). It is also seen as a community-building tool. Community currency isn’t new. In fact, it wasn’t until 1913 that the Federal Reserve Act mandated a central banking system. Before that Act, currency in the U.S. was based on everything from lumber to land. Then, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, scrip was often issued and exchanged for goods and services when federal dollars were scarce.

Examples include wooden money in Tenino, WA; cardboard money issued in Raymond, WA with a picture of a big oyster on the back; and corn-backed money in Clear Lake, IA. Scrip was even issued by Vassar seniors that consisted of pea green, blue, and yellow cards. Scrips were used to pay teachers in Wildwood, NJ; to make the payroll in Philadelphia and numerous other cities and towns across the country. Scrips were issued by state governments, school districts, merchants, business associations, various agencies, even individuals.

Jane Jacobs, economist and author of Cities and the Wealth of Nations, sees the economy of a region as a living entity, and sees regional currency as an appropriate regulator of its life. She writes, "Currencies are powerful carriers of feedback information, and potent triggers of adjustments, but on their own terms. A national currency registers, above all, consolidated information on a nation’s international trade."

Community currency is a tool that can help revitalize local economies by encouraging wealth to stay within a community rather than flowing out. It provides valuable information about the community’s balance of trade. For example, if a currency is valued only in a certain region, then it cannot be used for goods or services from outside that region (unless the recipient agrees to spend it in the region of origin).

Today’s community currencies, like those of the Depression, are varied and diverse. Some are true currencies; i.e. they physically exist and are traded for goods and services like federal dollars. Other systems are actually barter or work exchange networks with no physical currency exchanged. Still others resemble the scrip common during the Depression.

The "rules" for these currencies also vary, depending on the needs and desires of community members. What they have in common is a commitment to community building, to supporting what’s local, and to gaining a greater understanding of the role of economics and money in our daily lives. Local currencies are backed by something tangible that the community agrees has value, as the examples that follow illustrate.

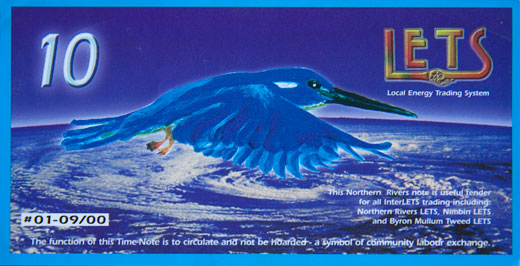

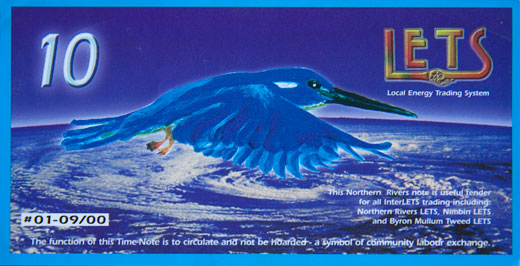

LETS

LETS was created by Michael Linton in the Comox Valley of British Columbia in 1983. As an unemployed computer programmer with an interest in community economics, Linton saw that many people were in a similar position: they had valuable skills they could offer each other yet had no money. He also saw the limitations of a one-on-one barter system. If a plumber wanted the services of an electrician, but the electrician didn’t need plumbing help, the transaction couldn’t take place. LETS solves the problem by opening the exchange to a whole community of members.

Here’s how it works: Joe cuts firewood for Mary, who is a welder. Mary is now in debt to the system for the amount of the transaction ($75.00, let’s say), and Joe’s account is credited for that amount. A few days later, Joe calls Mark for help fixing his car. Joe’s credit is reduced by the $50.00 Mark charged and Mark’s is credited with that amount. Then Mark wants some welding, calls Mary and so it goes. The unit of exchange, what Linton calls "the green dollar," remains where it is generated, providing a continually available source of liquidity. The ultimate resource of the community, the productivity, skills, and creativity of its members, is not limited by lack of money. And these resources are the "backing" behind green dollars.

Several years ago, Linton wrote, "Money is really just an immaterial measure, like an inch, or a gallon, a pound, or degree. While there is certainly a limit on real resources -- only so many tons of wheat, only so many feet of material, only so many hours in the day -- there need never be a shortage of measure. (No, you can’t use any inches today, there aren’t any around, they are all being used somewhere else.) Yet this is precisely the situation in which we persist regarding money. Money is, for the most part, merely a symbol, accepted to be valuable generally throughout the society that uses it. Why should we ever be short of symbols to keep account of how we serve one another?"

In LETS, green dollars exist only as records kept on paper or on a computer database. Transactions are reported by phone to a central coordinator and members receive monthly statements and regular listings of members and their services. The original system in the Comox Valley started with just six people and four years later had as many as 500 members, including several businesses. Unfortunately, when finances in the Valley improved, LETS shrunk, although I hear it is now being revived.

Today there are numerous LETSystems, and variations on the theme in the U.S., Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. There are nearly 200 LETS in Britain.

Activist Nick England says that in Britain, "LETSystems are part of a wider movement toward permaculture and sustainability. They are inherently ecological, since they are needs-oriented and local. At first they work alongside the conventional economy but, as more networks form, they could bring about a network of sustainable communities. The one we started in our city now has nearly 100 members offering bicycle and car maintenance, music and language lessons, gardening, childcare, food and food processing, craftwork, manual labor, massage, and many other resouces."

Joel Russ is the co-founder of a LETS group in the Slocan Valley (British Columbia) that has been around for close to three years now. Joel writes, "[A] problem with conventional money is that (as part of the vast international market system) it tends to flow to where it makes the most money -- usually to the biggest cities, the trade and industrial centers, a good share of it finally coursing into and through the bank accounts of very wealthy weapons and oil peddlers.

"Such, after all, is the immense scope of The System. But most of us live closer to the other end of the scale, and we voluntary simplicitists can often feel we have too little money for our needs. A LETSystem keeps local energy local, rather than pouring it (in dollar-bill form) out of the community. LETS thus supports a truly local economy. Those who believe in reducing their participation in the standard currency system, thereby contributing to reducing The System’s pressure on natural systems, find LETS participation a meaningful ecological gesture."

Australia offers a major LETS success story. When Britain joined the European Union’s Common Market, Australia lost its main export market. Food stocks destined for Britain had to be destroyed, and unemployment and bankruptcy became common. But LETS had found its way to Australia, providing welcome relief to people who became involved in these non-monetary economies that developed in scattered communities around the country. In 1992, the Australian government invited Linton to set up LETS throughout the country, with the government providing funds for education, publicity, computer equipment, and other expenses. Businesses that joined, typically accepting 25 percent payment in LETS, found that their business increased.

In Western Australia, it is estimated that LETSystems pumped the equivalent of A$3 million into the economy, which grew to include 1,500 businesses the first year. The same "rule" applies to these systems: businesses can only spend LETS units locally. As a result, some give their earnings to charity and qualify for a tax rebate. LETS earnings donated to charity have enabled churches to help unemployed youth and provide other necessary services. Patrica Knox, writing in the Winter 1995 Earth Island Journal observes, "If the global economy crashes, Australia would be the country most likely to survive, having developed a thriving alternative economy."

LETS is not without its problems, of course. One of the most commonly asked questions is, "What about a person who spends heavily in the system and then is unable or unwilling to repay?" In the early days Linton said this didn’t happen often enough to be an issue, "The simple willingness to undertake a commitment to provide fair value to another member of the community at some later date ensures that anyone who acts in good faith can spend as they need.

Of course, a person who consistently fails to redeem their promises will thereby lose this opportunity, but at least the situation is of their own making. Most people who have no money are poor through no fault of their own. People suffer because they are so dependent on things beyond their control, like the export market, the bank rate, general consumer demand, commodity speculation, etc. Every transaction in a LETSystem is a matter of mutual consent."

But as the years passed, some systems, including the one in the Comox Valley, experienced high levels of debt. The group in the Slocan Valley decided to impose a 300-clam (the name of their currency) limit for the first year of membership, and 500 thereafter in response to problems posed by transiency within the community.

Another issue is how to determine the value of a green dollar (or a clam, acorn, or whatever name a currency is given). Most systems start out with one unit of their currency equaling one federal dollar. Yet many, especially people who feel the inequities of the paid wage system, want to move away from the conventional value system. Why, they ask, should one person’s labor be worth three or four times what someone else earns? Alternative systems, they argue, should address these inequities directly.

There are many reasons given to justify keeping a LETS unit relatively equal to a dollar, especially at first. For one thing, it’s what most of us are used to. If a community desires business participation, as most do, a federal dollar equivalent seems almost essential. Yet, even without consciously attempting to de-link the value of LETS from the federal dollar, LETS members come to value each other as people rather than as the dentist, plumber, lawyer, babysitter, or gardener, and they begin to trade more on an hour for hour basis. After a while people get creative. Too often we value ourselves only for what we are paid to do. We forget that our hobbies and other skills and interests are also gifts we can offer to community members. The simplistic new age slogan, "do what you love and the money will follow" actually has a chance of success in a system that values people over profit and isn’t ruled by scarcity.

LETSystems have a tendency to flourish during hard financial times and shrink when the economy turns around. Probably because it’s easier (read more expedient) to pay cash for something than to arrange to work at a later date in exchange for it. Plus, if we have more money it’s probably because we are working more hours for it, leaving fewer hours for LETS commitments. So, for LETS to play a major role in transforming our economy into one that is locally/regionally based and community controlled, members must make a commitment to it in both good and bad times. Without this commitment, LETS’s real potential to contribute to systemic change (rather than just creating more purchasing power) is undermined.

Scrip

The E. F. Schumacher Society, based in Great Barrington, MA, has been at the forefront of community-based economics since it was founded in 1980 to promote the work of E. F. Schumacher (author of Small is Beautiful). Robert Swann, the Society’s president, was involved in economic alternatives for years before the Society was founded. With Ralph Borsodi, he pioneered the community land trust model in the 1960s, and in the 1970s developed the revolving loan fund model with the Institute for Community Economics. In addition to questioning conventional private land ownership and project financing (both of which are skewed to benefit monied interests over the rest of us), Swann has tirelessly sought alternatives to the federal currency system.

In 1989, a local deli, well loved by many people in Great Barrington, had to relocate because its lease was running out and a new lease would double the rent. Frank, the owner of the deli, went to several banks to borrow money to move to another location and was turned down. Finally he approached SHARE (Self-Help Association for a Regional Economy), the Schumacher Society’s loan-collaterialization program. Susan Witt, SHARE’s administrator, suggested that he issue his own currency -- Deli Dollars -- and sell them to his customers to raise the money he needed. Each note sold for $9 and could be redeemed for $10 worth of food, and was dated so that redemption was staggered over time.

In 1989, a local deli, well loved by many people in Great Barrington, had to relocate because its lease was running out and a new lease would double the rent. Frank, the owner of the deli, went to several banks to borrow money to move to another location and was turned down. Finally he approached SHARE (Self-Help Association for a Regional Economy), the Schumacher Society’s loan-collaterialization program. Susan Witt, SHARE’s administrator, suggested that he issue his own currency -- Deli Dollars -- and sell them to his customers to raise the money he needed. Each note sold for $9 and could be redeemed for $10 worth of food, and was dated so that redemption was staggered over time."I put 500 notes on sale and they went in a flash. It was astonishing," Frank said. Before long, Deli Dollars were turning up all over town as people exchanged them instead of U.S. dollars for goods, services, or debts. In effect these paper notes, which were essentially nothing more than small, short-term loans from customers, became a form of community currency. They so excited the people of Great Barrington that they were followed by Farm Preserve Notes issued cooperatively by Taft Farms and the Corn Crib. Each farm raised about $3,500 the first year and issued new notes in succeeding years. Five other businesses also issued scrip, including the Monterey General Store and Kintaro (a Japanese restaurant and sushi bar). Together, these businesses raised thousands of dollars to finance their operations that they couldn’t have obtained through conventional sources. These success stories drew the attention of the New York Times, Washington Post, ABC, NBC, CNN, and Tokyo television and have inspired projects around the country.

Susan Witt sees these programs as part of a larger strategy to strengthen regional economies. She explains, "Basically, we’re looking to find the way in which wealth generated in the region can be kept in the region. Our local banks, which did a very good job of that in the past, have now been bought up by larger and larger holding companies. So the deposits, the earnings generated in rural regions and inner cities, become like the wealth generated in Third World areas: It tends to all flow out into a few central, international, urban centers.

"A regional currency is ultimately the way that communities can regain independence and begin to unplug from the federal system: to take back their rights to generate their own regional currencies. As our area of Great Barrington gets used to exchanging Berkshire Farm Preserve Notes and Deli Dollars, we hope it will be the beginning of a true, independent, regional currency that’s broadly circulated."

ITHACA HOURS

In the U.S., the community currency receiving the most attention these days is the ITHACA HOUR in Ithaca, New York. The system was created in 1991 by Paul Glover, a community economist, ecological designer, and author of Los Angeles: A History of the Future. Since then, close to $50,000 in local currency has been issued to over 900 participants and has been used by hundreds more. While this may not sound like much, these HOURS have circulated within the community many times generating hundreds of thousands of dollars of local trading, adding substantially to what Paul calls "our grassroots national product."

Each ITHACA HOUR is equivalent to $10.00 because that’s the approximate average hourly wage in Tompkins County. The notes come in five denominations from a two-HOUR note down to a one-eighth HOUR note, and the designs feature native flowers, waterfalls, crafts, farms, and people respected by the community. Since the currency must be easily distinguishable from federal currency, they are a slightly different size from federal bills and are multicolored, some are even printed on locally made watermarked cattail paper. Participants are able to use HOURS for rent, plumbing, carpentry, car repair, chiropractic, food (two large locally-owned grocery stores as well as farmer’s market vendors accept them), firewood, childcare, and numerous other goods and services. Some movie theaters accept HOURS as well as bowling alleys and the local Ben & Jerry’s.

Participants pay one U.S. dollar to join and receive four HOURS when agreeing to be listed as backers of the money. A free newsletter, Ithaca Money, is published six times a year, which lists a directory of members’ services and phone numbers, as well as related articles, ads, and announcements. Every eight months those listed may apply to be paid an additonal two HOURS for their continuing participation. This is how the supply of currency in the community is carefully and gradually increased.

While ostensibly everyone’s work is valued equally, some negotiation does take place for certain professions like dentists, lawyers, massage therapists, and the like who typically make more than $10 an hour. Glover explains, "With ITHACA HOURS, everyone’s honest hour of labor has the same dignity. Still, there are situations where an HOUR for an hour doesn’t work. For example, a dentist must collect several HOURS for each work hour because the dentist and receptionist and assistant are working together, using equipment and materials that they must pay for with dollars. So, a lot of negotiating must take place."

Potluck dinners are held monthly and it is at these gatherings that members get together and discuss HOUR-related business. Occasionally members decide to grant HOURS to a well-deserving community organization. So far, more than $4,000 has been donated to 20 community organizations. Members have plans to develop a community cannery, to start a recycling warehouse, and to buy land to be held in trust. "We regard HOURs as real money, backed by real people, time, skills, and tools," Glover states. Loans of HOURS are made without interest charges.

What about the federal government? Glover says their main concerns are that they have a design different than federal dollars and that it be counted as taxable income when accepted for trades or services of a taxable nature.

To make it easier for other communities to start similar systems, Glover has created a Hometown Money Starter Kit (for $25 U.S. dollars or 2.5 Ithaca HOURS) that explains step-by-step the start-up and maintenance of an HOUR system. The kit also includes sample forms, articles, insights, samples of HOURS, and back issues of Ithaca Money. Glover is also more than willing to answer questions by e-mail. The kit has been requested by 400 communities in 48 states and printed local currencies are in use in 21 communities, including Eugene, OR; Syracuse, NY; Butte County (CA); Santa Fe, NM; and Kansas City, MO. Several more communities are in the planning stages.

While local currency can be a lot of fun, it is also lots of hard work and responsibility. The group initiating the currency must be clear about what they are doing and why. In regions consisting of several smaller communities (as opposed to cities like Ithaca), organizing can be more difficult and deciding the boundaries of the currency can be difficult, too. Some federal dollars will be needed to print money, informational flyers, and member directories necessitating fundraising or grant writing.

Most community currency systems believe it is important to sign up several businesses in addition to individuals. Yet it’s important that trading not be confined to these establishments. After all, the point is to enhance community members’ ability to trade amongst themselves. Glover suggests restraining the per-purchase acceptance of local currency by prominent businesses to allow their capacity to spend local money to expand gradually, and encourages active outreach to bring in smaller businesses and individuals with diverse skills. However, logistics and technicalities aside, the most important thing before launching any currency system is to know your community. Lacking this, the first organizing task is to get out there and talk with folks to find out where they’re coming from and what they want. Your system can begin with a few pioneers and expand as the community gradually understands it.

Tool for change?

When people first discover community currency and understand a bit about how it works they are usually not inclined to be overly critical. It sounds so good, so freeing, in a sense, just what the doctor ordered to address the sicknesses and diseases caused by our current economy and dependence on federal dollars. Plus, the idea of printing your own money is exciting and powerful. But to activists seeking strategies that not only challenge the current system, but transform it, it’s important to look at currency systems with a critical eye.

What’s to prevent a system like HOURS from becoming just like federal money? Once people become used to it, won’t it feel like just another commodity to earn and spend? While the principle of "everybody’s work is equal" sounds good, the fact is the HOUR system admits this is true for some, but not all members. Where’s the equity in this? Another concern is the role of business. Will business participation limit the relationships between individuals in the system in favor of conventional consumer roles? How to value goods and services is also an issue. Should participants put a price on their services just like in the conventional money system or be more creative? Should an HOUR have any dollar value at all? Could it represent just an hour of time? Finally, if we really want to get away from the feelings of greed, competiton, scarcity, powerlessness, and inequity engendered by our conventional money system, why create another form of money? Why not just do away with currency totally and move toward a system that provides everyone with what they need in exchange for their labor?

The issue of scale is never easy either. Some favor large state or province-wide systems, others think the ideal size is at the neighborhood level. Most fall somewhere in between. Melissa MacDonald, a member of the Santa Fe Greens who created an HOURS system, says that although some people would like their system to become regional because people tend to come to Santa Fe for what they need, the Greens "view this as a problem contradicting the local focus of the currency; we would rather help other communities set up their own Hours projects."

The problem (and the beauty) of models like LETS or HOURS is the specifics. Therefore the answers to these questions really depend on the community implementing them. Whether a system is designed merely to increase buying power, or to put a monkeywrench into business-as-usual depends on the values and politics of those who create it. Today, most (if not all) groups currently involved in some kind of community currency system, whether the barter model or the HOUR model, have stated that community building is a major goal, if not the major goal of the project.

People also see community currencies as a means to create more self-reliant local and regional economies. Since community currencies can be spent only in the community or region they are issued, goods and services that are dependent on resouces from outside the region will have to be paid for in federal dollars. This can help people get a handle on the resources available locally versus those imported from other places.

The Rocky Mountain Institute’s Economic Renewal Program, designed to help people take charge of their community’s economy, recommends that people take an inventory of all community resources as a first step. Part of this inventory process is knowing what goods and services the community provides for itself and those it imports from elsewhere. This helps identify areas for potential development. For example, if a community imports 80 percent of its food and yet has agricultural land sitting fallow, an obvious tactic would be to put that land back into food production. Community currencies can provide similar information. A mechanic who has to import parts won’t be able to accept LETS "green dollars" or HOURS for those parts, but he or she can accept them for his or her time. This is not to say that the goal should be to produce everything we need in our community or region. This is neither practical nor, in some cases, desirable. But it does make sense to become more self-reliant in providing for daily needs.

"Rather than isolating communities," Glover explains, "local self-reliance gives them the strength to reach out to each other, to import and export more than before." Still it makes sense to substitute local production and labor for imports when the resouces and skills are available locally. In these days of global "free trade" when jobs are exported to countries with cheap labor and lax environmental regulations, it’s smart to create locally-owned enterprises that hire local people to provide for local needs.

Unlike conventional money that is based on scarcity and that fosters competition, community currencies are designed to include everyone who wants to participate. By doing so they take advantage of a wide range of skills and resources, unlike the conventional economy which values certain skills and devalues or ignores others. As mentioned earlier, federal dollars tend to flow out of local communities where they are needed the most to those who already control large pools of wealth like banks and corporations. The very nature of community currency prevents this outflow. Further, there is no benefit to hoarding huge numbers of HOURS since they are worth something only in local trade.

You can’t invest them in the stock market, they are worth nothing on international currency markets, and you probably wouldn’t want to will a bunch of them to your grandchildren (except as a matter of curiosity). "HOUR money has a boundary around it," Glover explains, "so HOUR labor cannot enrich people who then take our jobs away to exploit cheap labor elsewhere. It must be respent back into the community from which it comes. It does not earn bank interest so it is not designed for hoarding. It benefits us only as a tool for spreading wealth."

But what’s to prevent HOURS from becoming like any other establishment currency? The values and consciousness of its members. According to Glover, "Local currency activists generally seek to fundamentally transform society, rather than merely make it endurable." People starting currency systems must be very clear about what they are doing and why. If a goal is to change the system and move away from valuing people’s time and labor in dollars; if a goal is to build relationships within the community based on mutual respect and reciprocity then members have a responsibility to take steps along the way to ensure these goals are being acheived and not left behind in the excitement of printing money and expanding individual spending power.

For any project, currency or not, to realistically work for systemic change it is important for those implementing it to have an understanding of the larger picture of which their project is a part. In the case of currency, we need to understand the history of money and trade relationships. We need to have an understanding of the role of markets in creating communities and interpersonal relationships, not to mention the hidden and not-so-hidden agendas of national and international markets. To intentionally remove ourselves from these larger markets in favor of creating stronger local ones is a political statement with repercussions that extend beyond our local communities. Currency activists say, "Of course. That’s why we’re doing it."

But this may not be so obvious to people who join in after a system is set up and who view it mostly as a way of obtaining more buying power. The originators of currency systems have a responsibility to educate members regarding these larger issues. This is not to say everyone has to agree. But there should be an overarching vision that doesn’t get lost in the day-to-day practicalities.

Regarding the value of one person’s labor in relation to another and the inequities in our current system that seem to be carried into these alternatives (like the dentist getting paid several HOURS for one hour of work), the experience in many communities is that over time, as people get to know each other better, those higher paid professionals often lower their prices to system members. This happened in the original LETS in the Comox Valley, and it’s happening in Ithaca today.

Glover reports that some professionals charge one HOUR per hour voluntarily, in the spirit of the system. And a participant in Kansas City’s Barter Bucks project states, "I can make $40 per hour on the outside, but I accept $10 an hour in Barter Bucks because I believe in the idea of equal pay." The fact that these changes of heart are happening in some places doesn’t guarantee that they’ll happen where ever a community currency is implemented. But they are an indication that people’s good will and innate sense of cooperation are brought to life by a system that encourages them.

Glover reports that some professionals charge one HOUR per hour voluntarily, in the spirit of the system. And a participant in Kansas City’s Barter Bucks project states, "I can make $40 per hour on the outside, but I accept $10 an hour in Barter Bucks because I believe in the idea of equal pay." The fact that these changes of heart are happening in some places doesn’t guarantee that they’ll happen where ever a community currency is implemented. But they are an indication that people’s good will and innate sense of cooperation are brought to life by a system that encourages them.What about just getting rid of money all together? The LETSystems and other barter networks potentially offer a money-less alternative, though work is still valued in dollars, they just aren’t physically exchanged. Community currency models, as exciting and visionary as they may be, are not the final answer in our search for a more equitable exchange system. They are, perhaps, the first step on the path. And it makes sense to take it and see where it leads. As Dean Price, of Cascadia Hours in Eugene, OR, explains, "The currency has the effect of moving communities into a gift economy because the people using it would rather be in a gift economy anyway, where they do things for each other without paper going between them."

Susan Meeker-Lowry is the author of Economics as if the Earth Really Mattered and Invested in the Common Good (New Society Publishers).

From http://homepage.mac.com/forever.net/About/potential1995.html

Please Help Keep This Unique Site Online

Donate any amount and receive at least one New Illuminati eBook!

Images – http://www.dincolodebani.ro/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/barter.jpg

http://www.faylist.com/b4yold/barter.gif

http://pacific-edge.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Local_currency_LETS4.jpg

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg_I8YnJo39yrJAwpLkfL-fIIu2McAD0FRH1oCYNLfqcPiwwlPxwm15nlTGQ5H7b_B3zAkBOFFt2V5Kn6wwNqSMZottkWtouMNPx4pGAN2Sxh80WplaIe1TMbugI_DfBqof7UzvOspFy6Y/s400/barter.jpg

http://www.spiralseed.co.uk/artwork/6lets1.jpg

http://www.samarasproject.net/images/hours.jpg

http://andrewlowd.com/thesis/hour7.jpg

http://www.faylist.com/b4yold/barter.gif

http://pacific-edge.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Local_currency_LETS4.jpg

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg_I8YnJo39yrJAwpLkfL-fIIu2McAD0FRH1oCYNLfqcPiwwlPxwm15nlTGQ5H7b_B3zAkBOFFt2V5Kn6wwNqSMZottkWtouMNPx4pGAN2Sxh80WplaIe1TMbugI_DfBqof7UzvOspFy6Y/s400/barter.jpg

http://www.spiralseed.co.uk/artwork/6lets1.jpg

http://www.samarasproject.net/images/hours.jpg

http://andrewlowd.com/thesis/hour7.jpg

For further enlightening information enter a word or phrase into the search box @ New Illuminati or click on any label/tag at the bottom of the page @ http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

And see

New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

New Illuminati on Facebook - http://www.facebook.com/pages/New-Illuminati/320674219559

New Illuminati Youtube Channel - http://www.youtube.com/user/newilluminati/feed

The Her(m)etic Hermit - http://hermetic.blog.com

This material is published under Creative Commons Fair Use Copyright (unless an individual item is declared otherwise by copyright holder) – reproduction for non-profit use is permitted & encouraged, if you give attribution to the work & author - and please include a (preferably active) link to the original along with this notice. Feel free to make non-commercial hard (printed) or software copies or mirror sites - you never know how long something will stay glued to the web – but remember attribution! If you like what you see, please send a tiny donation or leave a comment – and thanks for reading this far…

From the New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

Hi, I was simply checking out this blog and I really admire the premise of Childcare sydney

ReplyDeleteAwesome work once again! I am looking forward for your next post On Plumbing Services In Monterey.

ReplyDeleteDr OBUDU have been a great doctor even know in the world, am here today to tell the world my testimony about how i was cured from herpes.i was having this deadly disease called herpes in my body for the past 6 years but now i know longer have it again. i never know that this disease have cure not until i meet someone know to the world called Dr OBUDU he cured me from herpes he have been great to me and will also be great to you too. i have work with other doctor but nothing come out. one day i did a research and came across the testimony of a lady that also have same disease and got cured by Dr OBUDU. then i contacted his email and told him my problem.he told me not to worry that he have the cure i didn't believe him when he said so because my doctor told me there is no cure.he told me i need to get a herbal medicine for the cure which i did and now am totally cured you can also be cured of any other diseases too if only you believe in him. contact him via email OBUDU.MIRACLEHERBALHOME@GMAIL.COM you can also call or whatsapp him true his mobile number +2347035974895

ReplyDelete