The Quest for Immortality:

Would You Want to Live Forever?

Senescence.

No, that’s not some new anti-ageing cream. That’s the very contrived and scientific word for growing old. More specifically it describes the gradual biological deterioration of cellular function, which in most living things means that after maturation, the entity in question experiences increased mortality in step with the passage of time.

It is senescence that causes your wrinkles and grey hairs and your stubborn spare tire, indirectly that is. It is the unavoidable process that allows the direct causes of those maladies to come about. And it is that unavoidable process that some people wish to…avoid.

Since the beginning of time, it seems, mankind has sought the key to immortality. Whether that be through the fountain of youth – one of Sir Isaac Newton’s favourite musings – or, more recently, through the efforts of the transhumanist society, who see things in a slight bit more realistic terms, but we’ll get to that.

Senescence doesn’t apply to all living creatures though, amazingly enough. There are certain taxa, mostly plants, but some animals as well, who do not suffer from an increased mortality as they age. In fact there are some forms of life that undergo a defined decrease in mortality the older they get. These rare creatures, as they mature from whatever prepubescent or larval form they initially hold, retain the ability to revert back into a pre-mature state of being, which by-passes the process of senescence altogether.

Some species of crab and lobster have this ability, as do a few others in the genus arthropoda, and there are several species of tree, fungus and shrubbery that exhibit an impressive resistance to time’s assault.

The reason for this highly coveted ability isn’t well understood. In fact, the reason for the reason for this ability is something of a mystery too. How it works, senescence that is – or biogerontology, if you prefer – is somewhat understood, in that there are many highly complex and hotly debated theories of senescence on the books at the moment, from Gene Regulation Theory to Chemical and/or DNA Damage theories. It’s generally accepted that there is something inherent to biology that affects the efficiency of cellular replication throughout the lifecycle of any creature, it’s just, what that something is, isn’t readily agreed upon.

Here’s where it gets really interesting.

Medical science has studied this process and its attendant features for decades, in pursuit of both cosmetic cure-alls and more humane means of improving the length and quality of life. Human life that is. Some have taken that effort up as a sort of mantra, and have labelled their cause transhumanism. That is, whatever your preconceived understanding of the term may be, a concerted effort to defeat the sands of time and the effect they have on the human body. In short, they – transhumanists that is – wish to find a way to achieve immortality.

That’s a loaded word though, among a loaded sentence for that matter. We aren’t talking about the science fiction, romanticised notion of immortality. We aren’t talking about the Q from Star Trek, much as they might appreciate the sentiment. We’re talking about extending the lifespan of humans to an indefinite degree, through various technological and scientific means.

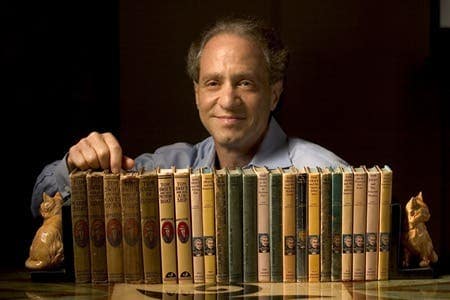

Quite often the goals of transhumanism are thought of in terms of cybernetics, a merging of technology and biology in an effort to find some permanence of life, though there are other means on the table. A new documentary film making rounds through the film festival circuit, The Immortalists, chronicles the quest of two transhumanist advocates and scientists as they seek out answers to the problem of senescence and ways to achieve immortality.

These men, William H. Andrews and Aubrey de Grey, whom are showcased in the film, approach the problem from drastically different positions. Andrews has studied biological methods of achieving a similar reversing of increased mortality, in much the same way as the species mentioned above. He believes that an artificial extension of telomeres in our DNA are the answer.

In the simplest terms, telomeres, which are the caps on the ends of DNA strands, appear to shorten as we age. Some researchers believe there is a direct correlation between this telomere shortening and senescence, and it follows, at least according to Andrews, that halting and/or reversing this shortening process will inherently alter or stop the aging process. He is currently seeking means to develop chemical medications that will reinforce telomeres, in effect making the patient immortal, of a fashion.

De Grey however, is taking a more space-age approach to the issue. He is calling for funding to further his research into medical nanotechnology. More specifically, he believes the answer is to develop and deploy microrobots that will work in the patient’s blood stream to repair and even replace damaged or aged cells, effectively, though artificially, sidestepping the aging process.

This research is already being done, but not for the purpose of achieving immortality. Several scientists at various universities and even pharmaceutical companies are attempting to use nanotechnology to combat cancer and even AIDS/HIV. It seems a natural extension of the research, and de Grey is appealing to the interests of Silicon Valley elites in an attempt to fund his research with specific transhumanist goals in mind.

In keeping with the title of this post, however…would you want to live forever?

Notwithstanding the fear we all have regarding death, are there valid reasons to want to extend the human lifespan to such artificially great heights?

There are certainly lots of reasons why we shouldn’t do this. Overpopulation is already an incredibly huge problem, do we really want to exacerbate that by eliminating the one part of life that mitigates our impact on this planet? (Death, I mean.) There’s also the issue of quality of life. Whether poverty, war, strife, or mental illness are symptoms of the overpopulation issue or not, they will certainly not be solved by prolonging the suffering of people over centuries, or even millennia. An eternity in squalor isn’t exactly an attractive idea, but this gives way to another issue, one you may not have considered yourself.

Who would be given the privilege of eternal life? Would this be a luxury afforded only to the elites of our society? If history is any indication, the answer to that question is a resounding yes, but what effect would that have on the already egregious divide between the so-called social classes? Would we end up with a ruling class of immortals, lording over a lower class of slaves? This line of reasoning becomes frightening fairly quickly, and though I’m not given to fear mongering, I can’t help but see this as a likely outcome.

Transhumanism is, or is supposed to be, a movement of equality. It’s supposed to be the pursuit of immortality for the benefit of all mankind, but, and even now, the movement is slowly becoming something of a shadow of the earlier notion of eugenics. Some have said that eugenics was a pragmatic effort to shore up the genetic potential of humanity in the face of what, at the time, was perceived as genetic flaws in our population. The real flaw, however, was always in thinking that those who are different are somehow less worthy of survival. This same flaw seems to be present in certain aspects of transhumanism.

It is said that this is an exciting time to be alive, and I couldn’t agree more. I’m not sure, though, that we’ve overcome the baser inequalities that are inherent to our species, and until we do, efforts such as the quest for immortality will always be marred by the pursuit of power and money and flawed ideology. We seem to be headed in the right direction, but we still have a long way to go.

From Mysterious Universe @ http://mysteriousuniverse.org/2014/03/the-quest-for-immortality-would-you-want-to-live-forever/

For more information about transhumanism see http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com/search/label/transhumanism

For more information about longevity see http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com/search/label/longevity

- See ‘Older Posts’ at the end of each section

Hope you like this

not for profit site -

It takes hours of work every day

to maintain, write, edit, research, illustrate and publish this website from a

tiny cabin in a remote forest

Like what we do? Please give enough

for a meal or drink if you can -

Donate any amount and receive at least one New Illuminati eBook!

Please click below -

For further enlightening

information enter a word or phrase into the random synchronistic search box @ http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

And see

New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

New Illuminati on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/the.new.illuminati

New Illuminati Youtube Channel - http://www.youtube.com/user/newilluminati/feed

New Illuminati on Google+ @ https://plus.google.com/115562482213600937809/posts

New Illuminati on Twitter @ www.twitter.com/new_illuminati

New Illuminations –Paintings in

Light by R. Ayana @ http://newilluminations.blogspot.com

The Her(m)etic Hermit - http://hermetic.blog.com

The Prince of Centraxis - http://centraxis.blogspot.com (Be Aware! This link leads to implicate &

xplicit concepts & images!)

DISGRUNTLED SITE ADMINS PLEASE NOTE –

We provide a live link to your original material on your site (and

links via social networking services) - which raises your ranking on search

engines and helps spread your info further! This site is

published under Creative Commons Fair Use Copyright (unless an individual

article or other item is declared otherwise by the copyright holder) –

reproduction for non-profit use is permitted & encouraged, if you

give attribution to the work & author - and please include a (preferably

active) link to the original (along with this or a similar notice).

Feel free to make non-commercial hard (printed) or software copies or

mirror sites - you never know how long something will stay glued to the web –

but remember attribution! If you like what you see, please send a donation (no

amount is too small or too large) or leave a comment – and thanks for reading

this far…

Live long and prosper! Together we can create the best of all possible

worlds…

From the New

Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com