The Amazing Motor That Draws Power From the Air

Ben Franklin invented it 223 years ago. Now we’re finding

overlooked possibilities in the electrostatic motor.

By C. P. GILMORE / PS Executive Editor and WILLIAM j. HAWKINS / PS Electronics Editor.

Would you believe an electric motor made almost entirely of plastic? That can run on power transmitted through open air? And sneak free electricity right out of the earth’s electrical field?

At the University of West Virginia we saw a laboratory full of such exotic devices spinning, humming, and buzzing away like a swarm of bees. They are electrostatic motors, run by charges similar to those that make your hair stand on end when you comb it on a cold winter’s day.

Today, we use electromagnetic motors almost exclusively. But electrostatics have a lot of overlooked advantages. They’re far lighter per horsepower than electromagnetics, can run at extremely high speeds, and are incredibly simple and foolproof in construction.

“And, in principle,” maintains Dr. Oleg Jefimenko, “they can do any- thing electromagnetic motors can do, and some things they can do better.”

Jewel-like plastic motors. Jefimenko puts on an impressive demonstration. He showed us motors that run on the voltage developed when you hold them in your hands and scuff across a carpet, and other heavier, more powerful ones that could do real work. Up on the roof of the University’s physics building in a blowing snowstorm, he connected an electrostatic motor to a specially designed earth-field antenna. It twirled merrily from electric power drawn out of thin air.

These remarkable machines are almost unknown today. Yet the world’s first electric motor was an electrostatic. It was invented in 1748 by Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin’s motor took advantage of the fact that like charges repel, unlike ones attract. He rigged a wagonwheel-size, horizontally mounted device with 30 glass spokes. On the end of each spoke was a brass thimble. Two oppositely charged Leyden jars—high-voltage capacitors —were so placed that the thimbles on the rotating spokes barely missed the knobs on the jars (see photo).

As a thimble passed close to a jar, a spark leaped from knob to thimble. That deposited a like charge on the thimble, so they repelled each other. Then, as the thimble approached the oppositely charged jar, it was attracted. As it passed this second jar, a spark jumped again, depositing a new charge, and the whole repulsion-attraction cycle began again.

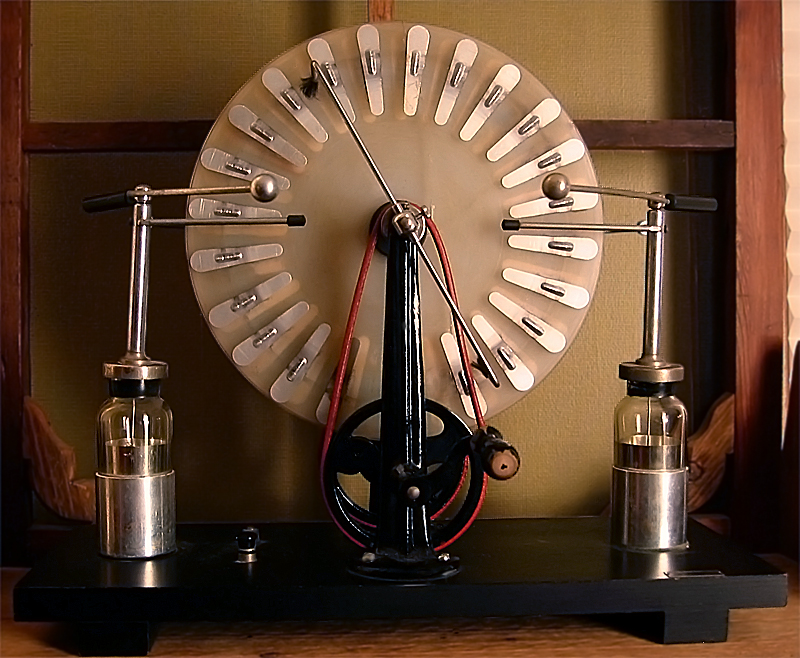

In 1870, the German physicist J. C. Poggendorff built a motor so simple it’s hard to see what makes it work. The entire motor, as pictured here, is a plastic disk (Poggendorff used glass) and two electrodes. The elec- trodes set up what physicists call a corona discharge; their sharp edges ionize air molecules that come in contact with them. These charged particles floating through the air charge the surface of the plastic disk nearby. Then the attraction-repulsion routine that Franklin used takes place.

A few papers on electrostatic motors have trickled out of the laboratories in recent years. But nobody really showed much interest until Dr. Jefimenko came on the scene.

The Russian-born physicist was attending a class at the University of Gottingen one day shortly after World War II when the lecturer, a Prof. R. W. Pohl, displayed two yard-square metal plates mounted on the end of a pole. He stuck the device outside and flipped it 180 degrees. A galvanometer hooked to the plates jumped sharply.

“I could never forget that demonstration,” said Jefimenko. “And I wondered why, if there is electricity in the air, you couldn’t use it to light a bulb or something.”

Electricity everywhere. The earth’s electrical field has been known for centuries. Lightning and St. Elmo’s fire are the most dramatic manifestations of atmospheric electricity. But the field doesn’t exist just in the vicinity of these events; it’s everywhere.

The earth is an electrical conductor. So is the ionosphere, the layer of ionized gas about 70 kilometers over our heads. The air between is a rather poor insulator. Some mechanism not yet explained constantly pumps large quantities of charged particles into the air. The charged particles cause the electrical field that Jefimenko saw demonstrated. Although it varies widely, strength of the field averages 120v per meter.

You can measure this voltage with an earth-field antenna—a wire with a sharp point at the top to start a corona, or with a bit of radioactive material that ionizes the air in its immediate vicinity. Near the earth, voltage is proportional to altitude; on an average day you might measure 1,200 volts with a 10-meter antenna.

Over the past few years, aided by graduate-student Henry Fischbach-Nazario, Jefimenko designed advanced corona motors. With David K. Walker, he experimented with electret motors. An electret is an insulator with a permanent electrostatic charge. It produces a permanent electric field in the surrounding space, just as a magnet produces a permanent magnetic field. And like a magnet, it can be used to build a motor.

Jefimenko chose the electrostatic motor for his project because the earth-field antennas develop extremely high-voltage low-current power; and—unlike the electromagnetic motor—that’s exactly what it needs.

The climactic experiment. On the night of Sept. 29, 1970, Jefimenko and Walker strolled into an empty parking lot, and hiked a 24-foot pole painted day-glow orange into the sky. On the pole’s end was a bit of radioactive material in a capsule connected to a wire. The experimenters hooked an electret motor to the antenna, and, as Jefimenko describes it, “the energy of the earth’s electrical field was converted into continuous mechanical motion.”

Two months later, they successfully operated a corona motor from electricity in the air.

Any future in it? Whether the earth’s electrical field will ever be an important source of power is open to question. There are millions—perhaps billions—of kilowatts of electrical energy flowing into the earth constantly. Jefimenko thinks that earth-field antennas could be built to extract viable amounts of it.

But whether or not we tap this energy source, the electrostatic motor could become important on its own.

In space or aviation, its extreme light weight could be crucial. Jefimenko estimates that corona motors could deliver one horsepower for each three pounds of weight.

They’d be valuable in laboratories where even the weakest magnetic field could upset an experiment.

Suspended on air bearings, they’d make good gyroscopes.

In a particularly spectacular experiment, Jefimenko turned on a Van de Graaff generator—a device that creates a very-high-voltage field. About a yard away he placed a sharp-pointed corona antenna and connected it to an electrostatic motor. The rotor began to spin. The current was flowing from the generator through the air to where it was being picked up by the antenna.

The stunt had a serious purpose: The earth’s field is greatest on mountaintops. Jefimenko would like to set up a large antenna in such a spot, then aim an ultraviolet laser beam at a receiving site miles away at ground level. The laser beam would ionize the air, creating an invisible conductor through apparently empty space.

To be sure, many difficulties exist; and no one knows for sure whether we’ll ever get useful amounts of power out of the air. But with thinking like that, Jefimenko’s a hard man to ignore.

From Popular Science (April 1971) via Rex Research @ http://www.rexresearch.com/stuff7/stuff7.htm#thomas

Electrostatic Generators

A Van de Graaff generator, for class room

demonstrations

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electromechanical generator that produces static electricity, or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back to the earliest civilizations, but for millennia it remained merely an interesting and mystifying phenomenon, without a theory to explain its behavior and often confused with magnetism. By the end of the 17th Century, researchers had developed practical means of generating electricity by friction, but the development of electrostatic machines did not begin in earnest until the 18th century, when they became fundamental instruments in the studies about the new science of electricity.

Electrostatic generators operate by using manual (or other) power to transform mechanical work into electric energy. Electrostatic generators develop electrostatic charges of opposite signs rendered to two conductors, using only electric forces, and work by using moving plates, drums, or belts to carry electric charge to a high potential electrode. The charge is generated by one of two methods: either the triboelectric effect (friction) or electrostatic induction.

Electrostatic machines are typically used in science classrooms to safely demonstrate electrical forces and high voltage phenomena. The elevated potential differences achieved have been also used for a variety of practical applications, such as operating X-ray tubes, medical applications, sterilization of food, and nuclear physics experiments. Electrostatic generators such as the Van de Graaff generator, and variations as the Pelletron, also find use in physics research.

Electrostatic generators can be divided into two categories depending on how the charge is generated:

- Friction machines use the triboelectric effect (electricity generated by contact or friction)

- Influence machines use electrostatic induction

Friction machines

History

Typical friction machine using a glass globe, common in the 18th century

Martinus van Marum's Electrostatic generator at Teylers

Museum

The first electrostatic generators are called friction machines because of the friction in the generation process. A primitive form of frictional machine was invented around 1663 by Otto von Guericke, using a sulphur globe that could be rotated and rubbed by hand. It may not actually have been rotated during use and was not intended to produce electricity (rather cosmic virtues),[1] but inspired many later machines that used rotating globes. Isaac Newton suggested the use of a glass globe instead of a sulphur one.[2] Francis Hauksbee improved the basic design,[3] with his frictional electrical machine that enabled a glass sphere to be rotated rapidly against a woollen cloth.[4]

Generators were further advanced when Prof. Georg Matthias Bose of Wittenberg added a collecting conductor (an insulated tube or cylinder supported on silk strings). Bose was the first to employ the "prime conductor" in such machines, this consisting of an iron rod held in the hand of a person whose body was insulated by standing on a block of resin.

In 1746, William Watson's machine had a large wheel turning several glass globes, with a sword and a gun barrel suspended from silk cords for its prime conductors. J. H. Winckler, professor of physics at Leipzig, substituted a leather cushion for the hand. During 1746, Jan Ingenhousz invented electric machines made of plate glass.[5] Experiments with the electric machine were largely aided by the discovery that a glass plate, when coated on both sides with tinfoil, can accumulate a charge of electricity when connected with a source of electromotive force.

The electric machine was soon further improved by Andrew (Andreas) Gordon, a Scotsman and professor at Erfurt, who substituted a glass cylinder in place of a glass globe; and by Giessing of Leipzig who added a "rubber" consisting of a cushion of woollen material. The collector, consisting of a series of metal points, was added to the machine by Benjamin Wilson about 1746, and in 1762, John Canton of England (also the inventor of the first pith-ball electroscope) improved the efficiency of electric machines by sprinkling an amalgam of tin over the surface of the rubber.[6] In 1768, Jesse Ramsden constructed a widely used version of a plate electrical generator.

In 1783, Dutch scientist Martin van Marum of Haarlem designed a large electrostatic machine of high quality with glass disks 1.65 meters in diameter for his experiments. Capable of producing voltage with either polarity, it was built under his supervision by John Cuthbertson of Amsterdam the following year. The generator is currently on display at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem.

In 1785, N. Rouland constructed a silk-belted machine that rubbed two grounded tubes covered with hare fur. Edward Nairne developed an electrostatic generator for medical purposes in 1787 that had the ability to generate either positive or negative electricity, the first of these being collected from the prime conductor carrying the collecting points and the second from another prime conductor carrying the friction pad. The Winter machine possessed higher efficiency than earlier friction machines. In the 1830s, Georg Ohm possessed a machine similar to the Van Marum machine for his research (which is now at the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany). In 1840, the Woodward machine was developed by improving the Ramsden machine, placing the prime conductor above the disk(s). Also in 1840, the Armstrong hydroelectric machine was developed, using steam as a charge carrier.

Friction operation

The presence of surface charge imbalance means that the objects will exhibit attractive or repulsive forces. This surface charge imbalance, which leads to static electricity, can be generated by touching two differing surfaces together and then separating them due to the phenomena of contact electrification and the triboelectric effect. Rubbing two non-conductive objects generates a great amount of static electricity. This is not just the result of friction; two non-conductive surfaces can become charged by just being placed one on top of the other.

Since most surfaces have a rough texture, it takes longer to achieve charging through contact than through rubbing. Rubbing objects together increases amount of adhesive contact between the two surfaces. Usually insulators, e.g., substances that do not conduct electricity, are good at both generating, and holding, a surface charge. Some examples of these substances are rubber, plastic, glass, and pith. Conductive objects in contact generate charge imbalance too, but retain the charges only if insulated. The charge that is transferred during contact electrification is stored on the surface of each object. Note that the presence of electric current does not detract from the electrostatic forces nor from the sparking, from the corona discharge, or other phenomena. Both phenomena can exist simultaneously in the same system.

Influence machines

History

Frictional machines were, in time, gradually superseded by the second class of instrument mentioned above, namely, influence machines. These operate by electrostatic induction and convert mechanical work into electrostatic energy by the aid of a small initial charge which is continually being replenished and reinforced. The first suggestion of an influence machine appears to have grown out of the invention of Volta's electrophorus. The electrophorus is a single-plate capacitor used to produce imbalances of electric charge via the process of electrostatic induction. The next step was when Abraham Bennet, the inventor of the gold leaf electroscope, described a "doubler of electricity" (Phil. Trans., 1787), as a device similar to the electrophorus, but that could amplify a small charge by means of repeated manual operations with three insulated plates, in order to make it observable in an electroscope. Erasmus Darwin, W. Wilson, G. C. Bohnenberger, and (later, 1841) J. C. E. Péclet developed various modifications of Bennet's device. In 1788, William Nicholson proposed his rotating doubler, which can be considered as the first rotating influence machine. His instrument was described as "an instrument which by turning a winch produces the two states of electricity without friction or communication with the earth". (Phil. Trans., 1788, p. 403) Nicholson later described a "spinning condenser" apparatus, as a better instrument for measurements.

Others, including T. Cavallo (who developed the "Cavallo multiplier", a charge multiplier using simple addition, in 1795), John Read, Charles Bernard Desormes, and Jean Nicolas Pierre Hachette, developed further various forms of rotating doublers. In 1798, The German scientist and preacher Gottlieb Christoph Bohnenberger, described the Bohnenberger machine, along with several other doublers of Bennet and Nicholson types in a book. The most interesting of these were described in the "Annalen der Physik" (1801). Giuseppe Belli, in 1831, developed a simple symmetrical doubler which consisted of two curved metal plates between which revolved a pair of plates carried on an insulating stem. It was the first symmetrical influence machine, with identical structures for both terminals.

This apparatus was reinvented several times, by C. F. Varley, that patented a high power version in 1860, by Lord Kelvin (the "replenisher") 1868, and by A. D. Moore (the "dirod"), more recently. Lord Kelvin also devised a combined influence machine and electromagnetic machine, commonly called a mouse mill, for electrifying the ink in connection with his siphon recorder, and a water-drop electrostatic generator (1867), which he called the "water-dropping condenser".

Holtz's influence machine

Between 1864 and 1880, W. T. B. Holtz constructed and described a large number of influence machines which were considered the most advanced developments of the time. In one form, the Holtz machine consisted of a glass disk mounted on a horizontal axis which could be made to rotate at a considerable speed by a multiplying gear, interacting with induction plates mounted in a fixed disk close to it. In 1865, August J. I. Toepler developed an influence machine that consisted of two disks fixed on the same shaft and rotating in the same direction.

In 1868, the Schwedoff machine had a curious structure to increase the output current. Also in 1868, several mixed friction-influence machine were developed, including the Kundt machine and the Carré machine. In 1866, the Piche machine (or Bertsch machine) was developed. In 1869, H. Julius Smith received the American patent for a portable and airtight device that was designed to ignite powder. Also in 1869, sectorless machines in Germany were investigated by Poggendorff.

The action and efficiency of influence machines were further investigated by F. Rossetti, A. Righi, and F. W. G. Kohlrausch. E. E. N. Mascart, A. Roiti, and E. Bouchotte also examined the efficiency and current producing power of influence machines. In 1871, sectorless machines were investigated by Musaeus. In 1872, Righi's electrometer was developed and was one of the first antecedents of the Van de Graaff generator. In 1873, Leyser developed the Leyser machine, a variation of the Holtz machine. In 1880, Robert Voss (a Berlin instrument maker) devised a form of machine in which he claimed that the principles of Toepler and Holtz were combined. The same structure become also known as the Toepler-Holtz machine. In 1878, the British inventor James Wimshurst started his studies about electrostatic generators, improving the Holtz machine, in a powerful version with multiple disks. The classical Wimshurst machine, that become the most popular form of influence machine, was reported to the scientific community by 1883, although previous machines with very similar structures were previously described by Holtz and Musaeus. In 1885, one of the largest-ever Wimshurst machines was built in England (it is now at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry).

In 1887, Weinhold modified the Leyser machine with a system of vertical metal bar inductors with wooden cylinders close to the disk for avoiding polarity reversals. M. L. Lebiez described the Lebiez machine, that was essentially a simplified Voss machine (L'Électricien, April 1895, pp. 225–227). In 1894, Bonetti[7] designed a machine with the structure of the Wimshurst machine, but without metal sectors in the disks. This machine is significantly more powerful than the sectored version, but it must usually be started with an externally applied charge.

In 1898, the Pidgeon machine was developed with a unique setup by W. R. Pidgeon. On October 28 that year, Pidgeon presented this machine to the Physical Society after several years of investigation into influence machines (beginning at the start of the decade). The device was later reported in the Philosophical Magazine (December 1898, pg. 564) and the Electrical Review (Vol. XLV, pg. 748). A Pidgeon machine possesses fixed inductors arranged in a manner that increases the electrical induction effect (and its electrical output is at least double that of typical machines of this type [except when it is overtaxed]).

The essential features of the Pidgeon machine are, one, the combination of the rotating support and the fixed support for inducing charge, and, two, the improved insulation of all parts of the machine (but more especially of the generator's carriers). Pidgeon machines are a combination of a Wimshurst Machine and Voss Machine, with special features adapted to reduce the amount of charge leakage. Pidgeon machines excite themselves more readily than the best of these types of machines. In addition, Pidgeon investigated higher current "triplex" section machines (or "double machines with a single central disk") with enclosed sectors (and went on to receive British Patent 22517 (1899) for this type of machine).

Multiple disk machines and "triplex" electrostatic machines (generators with three disks) were also developed extensively around the turn of the 20th century. In 1900, F. Tudsbury discovered that enclosing a generator in a metallic chamber containing compressed air, or better, carbon dioxide, the insulating properties of compressed gases enabled a greatly improved effect to be obtained owing to the increase in the breakdown voltage of the compressed gas, and reduction of the leakage across the plates and insulating supports. In 1903, Alfred Wehrsen patented an ebonite rotating disk possessing embedded sectors with button contacts at the disk surface. In 1907, Heinrich Wommelsdorf reported a variation of the Holtz machine using this disk and inductors embedded in celluloid plates (DE154175; "Wehrsen machine"). Wommelsdorf also developed several high-performance electrostatic generators, of which the best known were his "Condenser machines" (1920). These were single disk machines, using disks with embedded sectors that were accessed at the edges.

Modern electrostatic generators

Electrostatic generators had a fundamental role in the investigations about the structure of matter, starting at the end of the 19th century. By the 1920s, it was evident that machines able to produce greater voltage were needed. The Van de Graaff generator was developed, starting in 1929, at MIT. The first model was demonstrated in October 1929. The basic idea was to use an insulating belt to transport electric charge to the interior of an insulated hollow terminal, where it could be discharged regardless of the potential already present on the terminal, that does not produce any electric field in its interior.

The idea was not new, but the implementation using an electric power supply to charge the belt was a fundamental innovation that made the old machines obsolete. The first machine used a silk ribbon bought at a five and dime store as the charge transport belt. In 1931 a version able to produce 1,000,000 volts was described in a patent disclosure. Nikola Tesla wrote a Scientific American article, "Possibilities of Electro-Static Generators" in 1934 concerning the Van de Graaff generator (pp. 132–134 and 163-165). Tesla stated, "I believe that when new types [of Van de Graaff generators] are developed and sufficiently improved a great future will be assured to them".

High-power machines were soon developed, working on pressurized containers to allow greater charge concentration on the surfaces without ionization. Variations of the Van de Graaff generator were also developed for Physics research, as the Pelletron, that uses a chain with alternating insulating and conducting links for charge transport. Simplified Van de Graaff generators are commonly seen in demonstrations about static electricity, due to its high-voltage capability, producing the curious effect of making the hair of people touching the terminal, standing over an insulating support, stand up.

Between 1945 and 1960, the French researcher Noël Felici developed a series of high-power electrostatic generators, based on electric excitation and using cylinders rotating at high speed and hydrogen in pressurized containers.

Fringe

science and devices

See also

- Electrostatic motor

- Electrometer (also known as the "electroscope")

- Electret

- Static electricity

References

1.

See

Heathcote, N. H. de V.: "Guericke's sulphur globe", Annals of Science

6 (1950), p. 293-305; Zeitler, Jürgen: "Guerickes Weltkräfte und die

Schwefelkugel", Monumenta Guerickiana 20/21 (2011), p. 147-156; and Schiffer, Michael Brian (2003). Bringing

the Lightning Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of

Enlightenment. Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24829-5.,p.18-19

3.

Hauksbee,

Francis (1709). Psicho-Mechanical Experiments On Various Subjects. R.

Brugis.

4.

Stephen

Pumfrey, ‘Francis Hauksbee (bap. 1660, died 1713)’, Oxford Dictionary of National

Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2009

5.

Consult Dr. Carpue's 'Introduction to Electricity

and Galvanism,' London 1803.

6.

Maver, William

Jr.: "Electricity, its History and Progress", The Encyclopedia

Americana; a library of universal knowledge, vol. X, pp. 172ff. (1918). New

York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp.

7.

http://www.coe.ufrj.br/~acmq/bonetti.html

Instructions for building a Bonetti machine

From Wikipedia @ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrostatic_generator

And see Static Electricity Misconceptions @ http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com/2009/02/static-electricity-misconceptions-how.html

For more information about forms of wireless electricity see http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com/search/label/wireless%20electricity

- Scroll down through ‘Older Posts’ at the end of each section

Hope you like this

not for profit site -

It takes hours of work every day

to maintain, write, edit, research, illustrate and publish this website from a

tiny cabin in a remote forest

Like what we do? Please give enough

for a meal or drink if you can -

Donate any amount and receive at least one New Illuminati eBook!

Please click below -

Xtra Images – http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/Wimshurst.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Cuneus_discovering_the_Leyden_jar.png

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Cuneus_discovering_the_Leyden_jar.png

For further enlightening

information enter a word or phrase into the random synchronistic search box @ http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

And see

New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

New Illuminati on Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/the.new.illuminati

New Illuminati Youtube Channel - http://www.youtube.com/user/newilluminati/feed

New Illuminati on Google+ @ https://plus.google.com/115562482213600937809/posts

New Illuminati on Twitter @ www.twitter.com/new_illuminati

New Illuminations –Art(icles) by

R. Ayana @ http://newilluminations.blogspot.com

The Her(m)etic Hermit - http://hermetic.blog.com

The Prince of Centraxis - http://centraxis.blogspot.com (Be Aware! This link leads to implicate & xplicit

concepts & images!)

DISGRUNTLED SITE ADMINS PLEASE NOTE –

We provide a live link to your original material on your site (and

links via social networking services) - which raises your ranking on search

engines and helps spread your info further! This site is

published under Creative Commons Fair Use Copyright (unless an individual

article or other item is declared otherwise by the copyright holder) –

reproduction for non-profit use is permitted & encouraged, if you

give attribution to the work & author - and please include a (preferably

active) link to the original (along with this or a similar notice).

Feel free to make non-commercial hard (printed) or software copies or

mirror sites - you never know how long something will stay glued to the web –

but remember attribution! If you like what you see, please send a donation (no

amount is too small or too large) or leave a comment – and thanks for reading

this far…

Live long and prosper! Together we can create the best of all possible

worlds…

From the New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

I see many of your articles republished on Philisopher's Stone UK, and am always interested and start reading them there. Then I come to this site with the dreadful, unreadable font and have to stop reading. For god's sake, change your damn font. It's just not effective.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the well meaning advice. This is a reference site. If we took all simillar advice we'd use a normal boring font, published in black on white with no stellar backround - and we'd look and feel just like every other prosaic anodyne site on the web. No doubt we'd receive many more views from culturally challenged people, too. Those who dislike the papyrus font merely need to remove it from their system - then they'll receive this (and all other sites that use it) in a simpler font. The layout is designed to alter rote hypnagogic reading habits to make the reader focus - and to subtly alter and expand consciousness. However - you'll receive a simpler format if you subscribe via rss or click on the link to the original article at the end of most posts.

DeleteI like the font.

DeleteCOPY TEXT YOU WANT THEN PASTE IN WORDPAD

Delete