Animal Minds

Our Planetary Companions Are Very Like Us

Darwin's theory sparked a revolution in how we look at ourselves and our world. A key contention is that human and animal intelligence vary in degree, rather than in kind. Anyone who lives with a cat, a dog or some other kind of animal must surely be convinced that animals are conscious, and no-one can have any doubts that our closest relative, the great apes, are conscious. Canadian journalist Dan Falk looks at what consciousness means in this context.

Dan Falk: I visited the Toronto Zoo last summer soon after they opened their new gorilla rain forest exhibit. The main attraction is a group of 8 western lowland gorillas including a hefty male named Charles who weighs in at nearly 200 kgs. Of course the zoo is full of wonderful creatures from around the world but the apes and chimps seem to hold a special appeal and I think that’s because they remind us so much of ourselves. After all, they are our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom.

When you watch the younger apes running and jumping, climbing trees and swinging on ropes you can’t help thinking how similar they are to children. When you look at their faces you see expressions that seem to match our facial expressions. Behind all of those similarities in behaviour is there also a similarity of mind? How close is the mind of an animal to the mind of a human being? With humans we like to use the word consciousness to describe our complex mental world. Now not everyone agrees on exactly how to define consciousness but most scientists would agree that it goes beyond just responding to our environment, that it involves more than just acting by instinct on what we take in with our senses.

We also have memories and emotions, we can form images in our minds, we can even form abstract concepts and communicate them using language - but can animals do some of those things? What degree of consciousness do they have? John Sorrell is a philosopher at the University of California in Berkeley, he’s written several influential books on the science of consciousness. He says the evidence for animal consciousness is all around us.

John Sorrell: There’s always some philosopher who says that animals can’t have consciousness. Well he hasn’t met my dog Ludwig. I mean, there just isn’t any doubt that Ludwig is conscious. Not just because he behaves in a conscious kind of way, but because I can see that his behaviour is connected to a machinery that’s relatively like mine: those are his eyes, that’s his ears, that’s his nose.

So the reason I’m so confident that some animals at least have consciousness is not just because they have similar behaviour but because I can see they’ve got a relevantly similar causal mechanism. Now, how far down the phylogentic scale does it go? We don’t know. I don’t think it’s useful right now to worry about are snails conscious, we just don’t know enough. But there isn’t any doubt that primates are conscious, go to any zoo.

Dan Falk: It may well be that some animals experience at least some form of consciousness. Perhaps it’s more evolved in some species than in others. Patricia Churchland is a Canadian philosopher based at the University of California in San Diego. She agrees that animals probably have some form of consciousness but it may not be the same as ours.

Patricia Churchland: My thought about consciousness is that it isn’t one single solitary capacity, that it’s made up of a variety of things; being aware of sensations and perception is one; paying attention is another, being able to imagine and reflect is another and the difference between being in deep sleep and being awake is yet another and so forth. So, granting that there is really a whole range of capacities that are involved in human consciousness undoubtedly there are differences between say, your consciousness and that of a chimpanzee or between that of a chimpanzee and a dog or a newt. But undoubtedly there are some shared features…

Dan Falk: And yet the case for animals having at least some degree of consciousness has been steadily building. For example, we know that dolphins have highly developed social skills that allow them to know their place within their pod; they may even have a basic kind of language. In Arizona there’s an African grey parrot named Alex who can name more than 40 different objects and identify colours and shapes as well as a young child. And certainly most pet owners would claim that their cat or dog not only shows emotions but sympathises with the emotions of its owner.

Some scientists would point to those examples as evidence for animal consciousness. Critics would say they are simply cases of instinctive behaviour or of training an animal to do tricks. But the question of language has drawn special attention from scientists.

Some scientists would point to those examples as evidence for animal consciousness. Critics would say they are simply cases of instinctive behaviour or of training an animal to do tricks. But the question of language has drawn special attention from scientists.

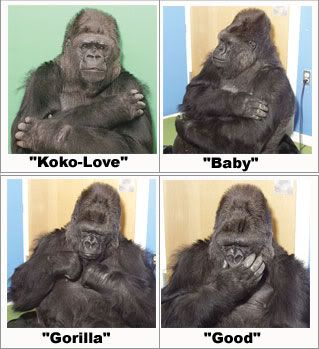

Researchers want to know if animal communication is more than just instinct or training, they want to know if it’s a true signal of sophisticated conscious thought. They’ve been focussing on the great apes, those primates most closely related to humans. A few of those creatures, the so-called linguistic apes, have been taught to communicate using sign language…

The ability to use language is just one aspect of consciousness, another aspect, perhaps the most basic is self consciousness. Some of the first experiments every done on animal cognition looked at this simple problem: the question of whether animals understand the distinction between themselves and others.

The simplest experiments involved nothing more than a mirror. Mark Hauser is a psychologist at Harvard University.

Mark Hauser: The mirror experience actually, as so often is the case, actually started with Charles Darwin. While he was working on the expression of emotions in man and animals he actually went to the one zoo and put a mirror in front of the orang-utan enclosure and simply watched what they did. And the orangs looked in the mirror and they often looked behind and reached behind the mirror and then they made facial expressions towards the mirror. So that was a big ambiguous, you know, the facial expressions could be interpreted as expressing towards another individual but it could also be explained as trying out to see what you look like. So those are simply ambiguous.

The simplest experiments involved nothing more than a mirror. Mark Hauser is a psychologist at Harvard University.

Mark Hauser: The mirror experience actually, as so often is the case, actually started with Charles Darwin. While he was working on the expression of emotions in man and animals he actually went to the one zoo and put a mirror in front of the orang-utan enclosure and simply watched what they did. And the orangs looked in the mirror and they often looked behind and reached behind the mirror and then they made facial expressions towards the mirror. So that was a big ambiguous, you know, the facial expressions could be interpreted as expressing towards another individual but it could also be explained as trying out to see what you look like. So those are simply ambiguous.

So it waited approximately a hundred years before the psychologist Gordon Gallup did a very creative experiment, which was to take a chimpanzee and show the chimpanzee the mirror, watch what they did - and the chimps did basically what the orang-utans did - and then after some period of time of exposure [he] anaesthetised the chimps, put one red mark over one eyebrow, one red mark over an ear, and these marks could not be smelt nor felt, there was no olfactory or tactile cues, and then when they awoke placed the mirror back in front of the chimpanzees and what they immediately do is selectively touch the red mark over the ear and the eyebrow and then begin to use the mirror to see parts of their body they’ve never seen before.

Now the reason why this is important is because it’s been shown, and it’s been shown continuously now, that many animals can use a mirror to find something hidden. That shows they can understand the sort of mechanics of the mirror but this experience says they can not only understand the mechanics of a mirror but they can understand the reflections of themselves.

Dan Falk: In the wake of those first experiments researchers have tried similar studies with all sorts of different animals, including humans. The great apes, chimpanzees, orang-utans or gorillas as well as children respond in the same way. When they see some kind of mark on their mirror image they’ll try to touch that mark. Lower species, including monkeys, don’t do this, they don’t seem to recognise that the image in the mirror is an image of themselves. The question is, what do these mirror tests reveal about the animals sense of self awareness. Mark Hauser.

Mark Hauser: When Gallup originally wrote on this problem, and I think he’s continued to argue this way, he basically argued that recognising one’s mirror image not only says that this animal has a sense of body image: that’s my body in the mirror, but also has a sense of self awareness. Now I think that’s an important distinction to make, because recognising that that’s my body to me doesn’t tell me anything about what the animal thinks about seeing its own body. Does it go, Hey, I’m kind of attractive, I’m ugly, I mean we don’t know, we’ve never learned a thing about that impression but that’s a sense of self awareness that’s the really interesting sense of self awareness.

Dan Falk: After looking at an animal's sense of self the next logical step is to look at whether it acknowledges others. We’re not just asking if it can interact with other animals, obviously every animal on the planet does that, we want to know does an animal understand that some other animal may feel what it feels, that it might see or hear or know what it sees, or hears, or knows.

Now the reason why this is important is because it’s been shown, and it’s been shown continuously now, that many animals can use a mirror to find something hidden. That shows they can understand the sort of mechanics of the mirror but this experience says they can not only understand the mechanics of a mirror but they can understand the reflections of themselves.

Dan Falk: In the wake of those first experiments researchers have tried similar studies with all sorts of different animals, including humans. The great apes, chimpanzees, orang-utans or gorillas as well as children respond in the same way. When they see some kind of mark on their mirror image they’ll try to touch that mark. Lower species, including monkeys, don’t do this, they don’t seem to recognise that the image in the mirror is an image of themselves. The question is, what do these mirror tests reveal about the animals sense of self awareness. Mark Hauser.

Mark Hauser: When Gallup originally wrote on this problem, and I think he’s continued to argue this way, he basically argued that recognising one’s mirror image not only says that this animal has a sense of body image: that’s my body in the mirror, but also has a sense of self awareness. Now I think that’s an important distinction to make, because recognising that that’s my body to me doesn’t tell me anything about what the animal thinks about seeing its own body. Does it go, Hey, I’m kind of attractive, I’m ugly, I mean we don’t know, we’ve never learned a thing about that impression but that’s a sense of self awareness that’s the really interesting sense of self awareness.

Dan Falk: After looking at an animal's sense of self the next logical step is to look at whether it acknowledges others. We’re not just asking if it can interact with other animals, obviously every animal on the planet does that, we want to know does an animal understand that some other animal may feel what it feels, that it might see or hear or know what it sees, or hears, or knows.

An example of this is the question of empathy. Can an animal understand what one of its fellow animals is experiencing? In humans this develops only in late childhood but when it does it becomes a very strong response. When we see a starving person on television, for example, we don’t just say that person has a problem, we can really imagine what it would be like to be in that person’s situation. Can animals do that?

Mark Hauser describes an experiment that tested whether certain primates can feel empathy.

Mark Hauser: So you train a rhesus monkey to pull one of two levers to access to food. If the animal does this it gets food and the only way it can get food during a day is by pulling the levers, so it basically is self feeding itself. Once it learns this task, which it does very quickly, now you put another rhesus monkey, into the adjacent cage visible to this individual. Now the experimenter changes one of the levers so that when he pulls it, it shocks the animal next door in a very strong shock, so the consequences are very visible to the animal in charge of the levers.

Mark Hauser describes an experiment that tested whether certain primates can feel empathy.

Mark Hauser: So you train a rhesus monkey to pull one of two levers to access to food. If the animal does this it gets food and the only way it can get food during a day is by pulling the levers, so it basically is self feeding itself. Once it learns this task, which it does very quickly, now you put another rhesus monkey, into the adjacent cage visible to this individual. Now the experimenter changes one of the levers so that when he pulls it, it shocks the animal next door in a very strong shock, so the consequences are very visible to the animal in charge of the levers.

Here’s the remarkable result. The animal in charge of the levers will stop pulling either lever for five to twelve days: it’s functionally starving itself in order not to shock the guy next door. He will do that more if it’s a familiar cage mate than an unfamiliar rhesus monkey, and if you put in - and this is a little bit comical, but not really if you think about it - if you put a rabbit next door they won’t withhold at all. So it’s species specific; it depends on familiarity and it also depends on whether the animal pulling levers has had experience being shocked. So it really gets very, very close to what it’s like to have an experience like that.

Dan Falk: All of these experiments offer hints at just what it is that separates us from our primate cousins. They give us a glimpse of that period in our history some time between six and four million years ago when our ancestors the early hominids diverged from the great apes, or rather, the time when both the hominids and the great apes diverged from some common ancestor.

Dan Falk: All of these experiments offer hints at just what it is that separates us from our primate cousins. They give us a glimpse of that period in our history some time between six and four million years ago when our ancestors the early hominids diverged from the great apes, or rather, the time when both the hominids and the great apes diverged from some common ancestor.

But what was it that pushed us down the path towards to high level consciousness? What put us on the path to culture and civilisation but not those other primates? A lot of psychologists have said it must have been language but Herbert Terrace at Columbia has a different idea. He says there must have been an even earlier development in our psychology that paved the way for language. He calls it 'joint attention', the way that one creature can sense that his companion is aware of the same thing that he is,.

Herbert Terrace: In children you can see this develop very clearly. A six month old child will look at a particular object, say a rattle, and just look at it and a parent knows the child wants the rattle. A few months later the child will look at the rattle and then look up at the parent and back and forth indicating please give me the rattle. OK, that’s very much just what an ape would do. Later on, maybe twelve to eighteen months, the child will look at the rattle, look up at the parent to check, Do you see that? and when the parent indicates, Yes, I see that, the child will smile because now the child is no longer interested in the rattle per se, it could be the car outside, it could be the cat, but the child is checking, Does mummy see what I see, is it the same?

Herbert Terrace: In children you can see this develop very clearly. A six month old child will look at a particular object, say a rattle, and just look at it and a parent knows the child wants the rattle. A few months later the child will look at the rattle and then look up at the parent and back and forth indicating please give me the rattle. OK, that’s very much just what an ape would do. Later on, maybe twelve to eighteen months, the child will look at the rattle, look up at the parent to check, Do you see that? and when the parent indicates, Yes, I see that, the child will smile because now the child is no longer interested in the rattle per se, it could be the car outside, it could be the cat, but the child is checking, Does mummy see what I see, is it the same?

Now it’s very easy to put the label 'rattle' on that later on, or cat, but first there is this joint attention and without joint attention which doesn’t require language I don’t see how language could have emerged. Because I know that what I’m saying is going to be received by the listener unless I have a theory of mind that the listener sees the world in a way that overlaps with my view of the world.

Dan Falk: If Terrace is right, then some time in the last few million years our ancestors developed this capacity for joint attention and this special ability allowed us to develop language. But even though our species was the only one to develop a sophisticated use of language we should remember that that’s just one aspect of consciousness. Other animals may have other kinds of mental abilities that also contribute to consciousness. Patricia Churchland of University of Calofornia, San Diego;

Patricia Churchland: On the assumption that the human brain is a product of biological evolution, then it would be very surprising if we alone had a feature that encompassed attention, being able to do visual or other kinds of imagery, awareness of sensations and so forth. You see, I don’t think of consciousness as a light that’s either on or off and consequently, I suspect that probably your consciousness is different from the consciousness of a chimpanzee but it’s possibly also different from the consciousness of say a medieval nun or different from the consciousness of a stone age man.

Dan Falk: Learning about animal minds isn’t just an academic exercise for zoologists and psychologists. One obvious application is on the ethical front: if we can show that animals have sophisticated mental lives it could be used as an argument that they deserve better treatment. Of course, even the great apes aren’t human, but if they’re close to human then they deserve then they deserve something close to human rights. Another application is in anthropology. These studies can help to illuminate the lives of our earliest hominid ancestors, creatures that have left behind a few scattered bones but few other clues about their lives and almost no clues at all about their minds.

And finally, we might just learn something about consciousness itself. If we can learn about the differences between our minds and animal minds then we’ll have taken a small step towards understanding the greatest evolutionary gift of all – the gift of human consciousness. I’m Dan Falk.

Dan Falk: If Terrace is right, then some time in the last few million years our ancestors developed this capacity for joint attention and this special ability allowed us to develop language. But even though our species was the only one to develop a sophisticated use of language we should remember that that’s just one aspect of consciousness. Other animals may have other kinds of mental abilities that also contribute to consciousness. Patricia Churchland of University of Calofornia, San Diego;

Patricia Churchland: On the assumption that the human brain is a product of biological evolution, then it would be very surprising if we alone had a feature that encompassed attention, being able to do visual or other kinds of imagery, awareness of sensations and so forth. You see, I don’t think of consciousness as a light that’s either on or off and consequently, I suspect that probably your consciousness is different from the consciousness of a chimpanzee but it’s possibly also different from the consciousness of say a medieval nun or different from the consciousness of a stone age man.

Dan Falk: Learning about animal minds isn’t just an academic exercise for zoologists and psychologists. One obvious application is on the ethical front: if we can show that animals have sophisticated mental lives it could be used as an argument that they deserve better treatment. Of course, even the great apes aren’t human, but if they’re close to human then they deserve then they deserve something close to human rights. Another application is in anthropology. These studies can help to illuminate the lives of our earliest hominid ancestors, creatures that have left behind a few scattered bones but few other clues about their lives and almost no clues at all about their minds.

And finally, we might just learn something about consciousness itself. If we can learn about the differences between our minds and animal minds then we’ll have taken a small step towards understanding the greatest evolutionary gift of all – the gift of human consciousness. I’m Dan Falk.

Higher Level Cognition

Excerpts from an AAAS symposium on animal brains and behaviour

Edward Wasserman: We now have a fully developed science of comparative cognition, and the individuals from whom you're going to hear today are some of the leading experts in this field. The science of comparative cognition experimentally evaluates Darwin's hypothesis of mental continuity. It does so not on the basis of cute stories, although some of the evidence is cute to be sure, but on the basis of very carefully conducted scientific studies. So let me go on and tell you just a little bit about the research that I and my colleagues have been doing for some time. Our research studies what might be called abstraction or abstract behaviour in pigeons and baboons. Humans, for the longest period of time, have underestimated the intelligence of animals, and I think you're going to hear today evidence that these underestimations are not justified. But with regard to abstract thinking, it has been believed that humans are set apart from all other animals.

One cognitive capacity that's vital to human intelligence particularly is the ability to tell whether two or more items are the same or different. So two pennies would be the same, a dime and a nickel would be different. My colleagues and I have conducted extensive behavioural research into same-different discrimination in baboons and pigeons. We've used a variety of different experimental setups involving computerised joysticks and touch screens, and we've discovered that both baboons and pigeons readily learn and more importantly transfer same-different discriminations based on arrays of identical and non-identical items. This is the hallmark of a concept and the animals have passed this test with flying colours.

These findings have clear evolutionary significance. Higher level cognition was once believed to be the unique province of human beings, but we now know that baboons and pigeons show similar intellectual abilities. The roots of abstract thought may thus lie deep in our animal ancestry. These discoveries suggest that we humans should keep our egos in check, we are certainly not the most intelligent animals on Earth.

Robyn Williams: Thank you very much. Our next speaker is Nicola Clayton, Professor of Comparative Cognition and director of studies in natural sciences for Clare College, University of Cambridge.

Nicola Clayton: Thank you. Imagine if an alien had landed on Earth during our Stone Age past and had a peek at us. She'd probably have seen us as these almost hairless creatures, weak and wimpy, with a slow bipedal gait, and really thought the only thing going for us was our oversized brain. The mind is arguably the most distinctive and important feature of our own humanity, and yet we now know, as Ed pointed out, that a number of animals do indeed share a number of properties with us when it comes to minds, despite the lack of language, which is just what Darwin argued. In fact I would say that the last 20 years or so has really seen quite a major revolution in our understanding of the minds of other animals.

Traditionally research on animal cognition focused primarily on primates, and particularly on the great apes because they're our closest relatives, and it's been known for many years that chimpanzees share many cognitive abilities with us, including the use and manufacture of tools. And there's even some evidence now that they can save tools for later use, suggesting that they may even be capable of planning ahead, another feature that was thought to be unique to humans. And the common assumption was that intelligence has evolved just once, but members of the crow family are also capable of forethought and, as Alex will tell you in a moment, of using tools.

I shall argue that food-caching jays, a member of the crow family, can plan ahead for tomorrow's breakfast, and that they can protect their caches from being stolen by others. It was the first evidence of planning ahead in an animal. At first that was thought as being very surprising. You might wonder why. I think perhaps the whole idea about why planning was thought to be so special is best illustrated actually by a poem rather than by any scientific quote, and that's a story that Robbie Burns wrote in his lament Ode to a Mouse.

In this lament he just ploughed over a field mouse's nest, and he felt absolutely rubbish. It was dusk and he saw this mouse wander off into the wilderness, and he thought surely this mouse is going to die and it was all his fault, he'd destroyed the mouse's nest. And then suddenly a thought struck him and he started to smile, and he turned to the mouse and he said:

Still thou art blessed, compared with me!

The present only touches thee,

But, oh, I backward cast my eye

On prospects drear,

And forwards, though I cannot see,

I guess and fear.

So for Robbie Burns and for many psychologists and philosophers, planning ahead was thought to be something that was uniquely human and not without its consequences. Remorse and regrets and worry about the future were all things that were thought to be uniquely human. We now know that's not true.

The finding that crows are as intelligent as chimpanzees also has a number of implications, of course. For one thing I would argue that the derogatory term 'bird-brain' is obsolete, we should be thinking about 'brainy-birds', the other way around. And it also challenges the assumption about the evolution of our own intelligence. Indeed I've argued that when it comes to cognition, crows are feathered apes, and what's more they're right in front of your nose, they're in your backyard, you can see them everywhere.

This thesis raises two other important issues; one concerns the kind of a brain that can support intelligence, because the bird brain has a very different structure from that of mammals. The second issue is whether intelligence is a highly specialised trait or a more general ability. The 'out of Africa' hypothesis suggests that primate intelligence just evolved in one particular niche in the African savannah, whereas a much more general idea would be that it evolved in a range of environments, from land to air.

So perhaps it's just a small evolutionary accident that we ended up with a planet of the apes rather than a planet of the crows. And I'll finish with a quote. In the 1800s the Reverend Henry Beecher was of the opinion that 'if men had wings and wore black feathers, few of them would be clever enough to be crows.' Thank you.

Guests on Dan Falk’s program:

Dan Falk Freelance Writer - Print, Television, Radio Toronto Ontario Canada danfalk@pathcom.com |

John R Searle Professor of Philosophy University of California Berkeley searle@cogsci.berkeley.edu |

Further information:

John Searle http://socrates.berkeley.edu/%7Ejsearle/ |

Patricia S Churchland Professor of Philosophy University of California San Diego Tel: +1(858)822-1655 pschurchland@ucsd.edu |

Patricia Churchland http://philosophy.ucsd.edu/Faculty/ |

Herb Terrace Pshycholgist Columbia University New York Tel: +1 212 854 4544 Tel: +1 212 854 8785 terrace@columbia.edu |

Marc D Hauser Professor of Psychology 33 Kirkland Street Department of Psychology Harvard University Cambridge MA 02138 Office: +1 617 496 7077 Lab: +1 617 4953886 Fax: +1 617 496 7077 hauser@wjh.harvard.edu Robyn Williams’ GuestsEdward WassermanProfessor Experimental Psychology Iowa University Iowa City http://www.psychology.uiowa.edu/PeopleSearch/people/DeptWebpage.aspx?personId=138 Nicola Clayton Professor of Comparative Cognition Cambridge University UK http://www.psychol.cam.ac.uk/pages/staffweb/clayton/ Alex Kacelnik University of Oxford UK http://users.ox.ac.uk/~kgroup/people/alexkacelnik.shtml |

Edited from transcripts broadcast on 20/4/2002 and 21/2/2009 on ABC Radio National’s Science Show.

Images - http://blog.thirdeyehealth.com/images/animal-mind-1.jpg

http://media.photobucket.com/image/animal%20minds/redmoongraphicnovel/Koko_Vocab_4Signs.jpg

http://www.scientificamerican.com/media/inline/one-world-many-minds_1.jpg

For further enlightenment see –

The Her(m)etic Hermit - http://hermetic.blog.com

New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

New Illuminati on Facebook - http://www.facebook.com/pages/New-Illuminati/320674219559

This material is published under Creative Commons Copyright – reproduction for non-profit use is permitted & encouraged, if you give attribution to the work & author - and please include a (preferably active) link to the original along with this notice. Feel free to make non-commercial hard (printed) or software copies or mirror sites - you never know how long something will stay glued to the web – but remember attribution! If you like what you see, please send a tiny donation or leave a comment – and thanks for reading this far…

From the New Illuminati – http://nexusilluminati.blogspot.com

Welcome to brotherhood Illuminati where you can become

ReplyDeleterich famous and popular and your life story we be change totally my name is Dan Jerry I am here to share my testimony on how I join the great brotherhood Illuminati and my life story was change immediately . I was very poor no job and I has no money to even feed and take care of my family I was confuse in life I don’t know what to do I try all my possible best to get money but no one work out for me each day I share tears, I was just looking out my family no money to take care of them until one day I decided to join the great Illuminati , I come across them in the internet I never believe I said let me try I email them.all what they said we happen in my life just started it was like a dream to me they really change my story totally . They give me the sum of $1,200,000 and many thing. through the Illuminati I was able to become rich, and have many industry on my own and become famous and popular in my country , today me and my family is living happily and I am the most happiest man here is the opportunity for you to join the Illuminati and become rich and famous in life and be like other people and you life we be change totally.If you are interested in joining the great brotherhood Illuminati.then contact him whatsspa +2347051758952 or you need my assistance morganiilluminatirich@gmail.com